Works of art for which the reproduction rights have fallen into the public domain and that belong to French museums can be freely accessed and lawfully copied. Using a specific example, the author reviews the legal measures and obligations that govern copies since the Law of 4 January 2002 on literary and artistic ownership.

Article in La Revue Experts n° 80 – September 2008 © Revue Experts

In general, because only part of an expert’s time is spent on court-ordered missions, he must maintain his principal activity in order to remain at the top of his art. Thus, when a sculptor, an expert in works of art, is elbow deep in clay with his co-workers in his workshop intent on producing a monumental marble sculpture destined for future generations, we can but congratulate him before assessing the result. In the instant case, it was a copy of a 17th-century fountain in the park at the Palace of Versailles. Ordered by an Asian museum, it created some concerns for the relevant French administrative department that were not justified in terms of the law but understandable since the administration is responsible for the preservation of a showpiece of French heritage and it is natural to become attached to it. Given the arguments raised, emotions can, however, sometimes produce unjustified whims.

1. The facts

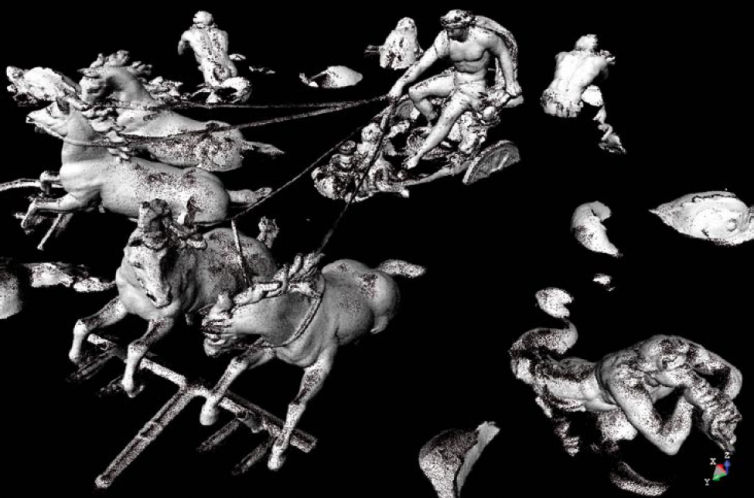

In January 2008, a colleague won a contract to sculpt a full-scale copy in Carrara marble of the Fountain of Apollo, a work by Jean-Baptiste Tuby created for Louis XIV and installed in the park at the Palace of Versailles between the ‘green carpet’ and the great canal (see photo). Even though no specific document seems to prove the exact reason why, the work of art was cast in lead and not marble like the remainder of the objects the subject of the initial royal orders situated closer to the palace. This alloy being less expensive than Carrara marble, it is clear that the purpose of the royal choice was to spend less money (see photo). The Asian museum’s management had initially hesitated between several other sculptures, principally Italian, including the Trevi or Bernini fountains in the Piazza Navona in Rome, both made of Carrara marble. Due to the case developed by the colleague, the Asian foundation management finally chose the work of Jean-Baptiste Tuby, wanting to place the 14-metre marble copy in the middle of a 38-metre pond that would welcome visitors to a large park, inviting them to cross an antique style bridge made of Carrara marble and decorated with twelve sculptures, also of antique style, in order to access the museum buildings currently under construction… By 2012, three thousand visitors per day will be visiting the park, obviously generating interest in Versailles and encouraging the visitors to come and admire the original work when the occasion arises. It is not difficult to see how the copy will provoke a cultural and economic bridge for Chinese visitors increasingly keen to discover Europe, especially since the new museum’s collections are mainly focused on French art.

2. The request for permission to access

It was in this context that our colleague, presented the order for the work, asked the curator of the Palace of Versailles for permission to take measurements of the work by Jean-Baptiste Tuby using a laser. It should be noted that this technique has no negative effects on lead. After a first contact by telephone with the sculpture’s curator, he was directed towards the sponsorship department, the manager of which evoked an initial price of €1,500,000 payable to the public institution under the right to reproduce. At the first meeting, that request was reduced to €1,000,000, the administrative authority imposing conditions that it retain control over the operations, that only one copy in clay be produced, that only one plaster cast be produced to serve as the master for the Italian sculptors and, lastly, only one copy be sculpted from Carrara marble. Our colleague noted that as J.-B. Tuby had died more than 70 years ago(1) (in 1700), the rights of reproduction had entered the public domain! The national museum curator agreed and rightly admitted not understanding how such price could be legitimately requested if both parties were not committed to a sponsorship agreement.

3. Sponsoring agreements

It is true that many agreements signed with private partners in order to restore the royal park and buildings are successful arrangements – the restoration of the ceiling in the Hall of Mirrors continues to bedazzle us. Due to actions by the Versailles Foundation or large companies, these agreements have enabled the restoration of many groves around the park as well as the protection of original works of art from bad weather by replacing them with marble powder cast versions. In exchange for each donation, estimated at approximately €100,000 per sculpture, the sponsor receives a copy of the sponsored work in synthetic resin and marble powder. Such sponsorships are fully justified as they satisfy the desire of the palace’s management to replace all of the marble sculptures in the park, from the antiques to those of the 17th century, with moulded works so that the originals can be sheltered from bad weather after being restored. The request by the copier is not, therefore, an issue of heritage conservation but an approach involving the exhibiting of an original work.

4. The discussions

The day after the meeting, a brief email, sent by the head of staff of the president of the National Public Works, rejected the request. The copying was not possible, according to the museum management, “in light of the details you provided during yesterday evening’s interview and the very advanced state of your project, with which, unfortunately, we have not been associated from the beginning, I regret to inform you that the Versailles public institution will not be able to assist in carrying out this project”. Any further discussion seemed closed and pointless, at least according to a bureaucrat. The stubborn artist did not see it that way. In multiple written exchanges, he referred to Arts. L.123-1, L.113-3, and L.121-3 of Law 92-597 of 1 July 1992(2) on artistic and literary ownership and the Law of 31 December 1921, as amended by the Law of 4 January 2002(3). The administration replied that it was still aware “of his desire to take digital measurements by laser of the Apollo Chariot sculpture by J.-B. Tuby for the purposes of producing a copy in Carrara marble”, but regretted that “the copy that you are going to produce will have significant differences to the original work of art, which goes against the mission of the Palace of Versailles to protect its collections, the Versailles public administrative institution being vested with this mission pursuant to its statutory Decree of 25 April 1995”. This ultimate argument was incorrect because even if that Decree clearly requires the institution to maintain and protect the park sculptures in particular, it does not prohibit copying or supervising the quality of such copies or even any potential interpretations that may result.

5. The compulsory inclusion of « copy »

The only constraint the museum management should have required was the application of the word “copy”(4) on each copied piece in a visible and indelible manner followed by the statement “after J.-B. Tuby”. Incidentally, the name of the sculptor, the copyright mark and the date of creation of the copy can appear, in compliance with the recommendations in the Code of Ethics for Art Foundries, Gallery Owners, Sculptors and French Auctioneers signed on 18 November 1993. We can only be surprised that the administration did not believe it necessary to remind the sculptor, in the letters it sent to him, of the terms of Decree 81-255 of 3 March 1981 enacted by its supervisory Ministry. It is clearly specified in Art. 8 that “any copy or other reproduction of a work of art must be described as such”. The sanctions that the person copying risks for breaching Arts. 8 and 9 of the Decree are the fines prescribed for the fifth category of offences(5). Was it an intentional omission or just ignorance of the law by the public administrative institution? In any case, a copying artist who is unaware of such legal obligations risks harsh fines and the confiscation of his work.

6. The legal proceedings

After more than three months of fruitless discussion, our sculptor colleague sent the institution manager a formal default notice by registered letter with acknowledgment of receipt in which, after having summarized the history of the facts, stated: “Never at any time did I ask for any assistance from your institution, only an authorization to obtain measurements […]. Consequently, this refusal is not based on good grounds and is in breach of Law 79-587 of 11 July 1979 on reasons given for administrative acts, as it lacks specific and genuine grounds”. As, in his opinion, this represented “an abuse of rights and a proven abuse of power”, our colleague asked the administration to reconsider its position “in order to avoid bringing the emerging dispute in the competent court”. On receipt of the registered letter with acknowledgment of receipt, the national museum had a period of two months to avoid the dispute being brought in the administrative courts.

7. The issuing of the authorization

The response came from the general manager who, after having defended the historical version of the acts undertaken by his institution, admitted that “nevertheless, the position of our institution should not in any circumstances been seen as a prohibition on copying the work of art, which you are perfectly free to do, so long as its integrity is respected”. It is important to emphasize that the concept of “respecting its integrity” remains subject to numerous interpretations. However, as the work of art in question is located in the middle of a pond that is full of water, the depth of which varies between 1.80 and 2 metres, our sculptor still needed specific authorization to use a power generator, a laser and a multitude of reflectors, etc, in order to be able to take a maximum number of measurements as possible so that the intended copy would be accurate and of good quality. Another letter was sent to the general manager thanking him for the above-mentioned stance by the institution, but reminding him that access to the small park in the palace was subject to an internal regulation on, among other things, the use of camera tripods. Our artist therefore had the honour of requesting “an authorization to allow him to carry out, in accordance with such provisions, the photometry necessary for the intended copy”. Finally, after a dozen written exchanges, he received the required authorization, worded as follows: “I inform you that you are free to obtain measurements of the Apollo fountain by Tuby using a laser”.

In conclusion

The tenacity of the sculptor, who firmly believed in his rights, won out over an administration presumably unhappy not that it was not supervising the copying or drawing any benefit from it. Although it is perfectly acceptable that the mission of the institution is, among other things, to obtain revenue through various means such as selling tickets, organizing shows, renting rooms or fundraising through sponsorship, French museums can no longer request copying fees in relation to works of art that have entered the public domain. The rights to photograph such items have also been free since the 2002 law referred to above. The intention of the legislator was to liberalize the economy and enable an expansion of the displaying of such works in order to facilitate their universal study and understanding. However, certain images of the Palace of Versailles can no longer be published, for example when Jeff Koons(6) set up an inflatable plastic lobster in the royal apartments or placed a giant dog’s head made of wire and decorated with greenery in front of the façade during the exhibition of his work in the museum and the park(7).

Footnotes

- Law of 27 March 1997, Art. L.123-1, then the Berne EC Directive 93/98 of 29 October 1993, Art. 1, paragraph 1, increasing the right to use reserved to the author or his right-holders to 70 years after his death. The exclusive right to reproduce, included in the ownership rights held by J.-B. Tuby or his right-holders, have, therefore, fallen into the public domain.

- Law 92-597 of 1 July 1992 on literary and artistic ownership: Art. L.113-3: “The intangible ownership defined in Art. L.111-1 is independent of the ownership of the physical object. As a result of the purchase, the buyer of the object is not vested with any of the rights provided in this Code, except in the situations provided in the second and third paragraphs of Art. L.123-4. Such rights subsist for the author or his right-holders who cannot, however, require the owner of the object to provide them with such object in order to exercise the said rights. However, in the event of a clear abuse by the owner preventing the exercising of the right to display, the Regional Court can order any appropriate measure, in compliance with Art. L.121-3. In the event of a clear abuse in the use or non-use of the right to display by the representatives of the deceased creator, pursuant to Art. L.121-2, the Regional Court can order any appropriate measures. The same applies if there is a conflict between the said representatives, if there are no known right-holders or in the event of absence or intestacy. Court proceedings can be brought by, in particular, the Minister for Culture. “A museum, as legatee of sculptures, is not the owner of any associated reproduction rights”… Civ 1st, 20 Dec. 1966: BVII. Civ.1, no. 558; D.1967. IR159; RTD com. 1967.744, obs. Desbois.

- Law of 31 December 1921, amended by the Law of 4 January 2002 on French museum collections. The courts and the Paris Court of Appeal have highlighted a limit to the extent of the fee demanded by the “French Museums” for services provided. Such fee cannot, under any circumstance, be defined as a right to an image or a right to reproduce (for a work of art that has fallen into the public domain). Where the item is in the public domain, the price remains limited and depends exclusively on the expenses incurred by the museum.

- Article 9 of Decree 81-255 of 3 March 1981. Any facsimile, overmould, copy or other reproduction of an original work of art under Art. 71 of Annex III to the General Tax Code that is produced after the date this Decree comes into force must be visibly and indelibly marked with the word “copy”.

- Article 10. Whoever breaches Arts. 1 and 9 of this Decree will be subject to the fines provided for the fifth category of offences.

- Jeff Koons, born in 1955, contemporary American artist whose provocative works of art, described as “kitsch art” by critics, have reached the peaks of international fame.

- Jeff Koons exhibition at Versailles from 10 September 2008 to 4 January 2009.

Reminder

Photographic, volumetric and audiovisual rights to reproduce a work of art fall into the public domain 70 years after the death of its author. They then become royalty-free.