Article in the Revue Experts n°114 of June 2014

On perusing this special edition on the duty to inform, readers will have understood that this obligation that a professional has towards his client, whether an individual, a company or a public entity, differs depending on the profession. It should first be remembered that such obligations are in fact only imposed on professionals: a private individual who sells one of his works of art is not subject to the duty to inform or advise.

The obligation to inform appears in French law at the beginning of the Consumer Code1. In the event of a dispute, it is, therefore, only the professional who has the burden of proving that he has complied with his obligations.

In negotiating the sales of ancient or recent works of art, for many the duty is seen in very vague if not inexistent terms. It is clear that a vendor has the legal obligation to keep accounts – a register of ‘second-hand items’, ie, antique works. But does he nevertheless have a duty to inform as defined by the case law for other professions? While the answer is most certainly yes, he does, however, rely more on a line of conduct or ethical principles rather than a defined law. Such duties, which originated from construction then commercial law, nonetheless apply de facto to the niche that is second-hand works of art or any recent artistic productions. The rare case law in this area counteracts the often unequal struggle between the private individual, the art lover and the professional decorator, antique dealer, auctioneer and expert. The involvement by such professionals is, however, essential, because the financial stakes are sometimes colossal and any breach can become very prejudicial.

The best-efforts obligation is nowadays clearly imposed under case law. For example, a professional who sells an antique Chinese vase without having taken the precaution of having it dated using thermoluminescence will be liable for his error if it is later discovered to be a fake. On the other hand, an expert who identifies a fake at a dealer’s or a specialised salon is not required to inform anyone. If he does so in front of witnesses, he even risks being investigated for slander and must then defend his opinion in court.

The most obvious duty is to inform the buyer of the exact condition and nature of the object being sold. The professional must inform the buyer in a clear and detailed manner: the subject of the work, the material used, the period or style, the presumed origin, numbering, etc, and its condition. These criteria have a primary role in all transactions for antiques or contemporary works. Restorations must also be mentioned because the authenticity of the work is in doubt where more than 30% of the work is the subject of more recent work.

Unless the unscrupulous professional avoids providing detail by including an evasive description on the invoice such as ‘statuette in metal’ or ‘sold as-is’, he has a duty to provide information on the work that he sells. The seller is, therefore, required to provide sufficient information to the buyer and to himself obtain information on the work being sold. He must, therefore, be aware as much as possible of its origin and history. He will ensure that the work is not the subject of any unsettled disputes, that his seller is clearly the full owner, that the work is free of any other rights under, for example, loans, securities or co-ownership.

When selling to a private individual, the professional can inquire as to where the work is to be held. Information must be provided on the materials used in the work if they do not permit it to be extensively exhibited. For example, an artist who sells a work in painted plaster (or other material that degrades when in contact with water) that is to be exhibited outside may be liable if the work suffers damage. Similarly, an antique dealer who sells a 18th-century item of inlaid and varnished furniture, knowing that his customer wants to place it on his yacht or next to a covered swimming pool, must inform him of the risks of accelerated deterioration. The era when the sale terminated the liability of the seller no longer exists.

Sometimes, a client may remain discrete as to the use of his purchase and the seller cannot, in such case, be liable for any incorrect use. But where the purchase is the subject of precise specifications, the seller must inform the buyer (in writing) if he considers that the place where the work is to be kept is likely to rapidly deteriorate the work. Water paintings, for example, should not be hung next to a bay window because the excessive sunlight will rapidly fade organic colours nor should paper works be hung in a bathroom (etchings, lithographs…) because the humidity encourages mould.

Certain artistic trades require a greater number of recommendations, such as gilding, the fabrication or restoration of gilded items of furniture and sculptures.

A gilder who does not inform his non-specialist client that exposing a sculpture to which gold leaf has been applied using a water preparation and stuck with a collagen (extract from rabbit skin) to bad weather is in breach of his duty to inform. He must give the client advice on the correct storing of the gilded object and that he should not have it cleaned with a water-based product. Or, if the client clearly wants to exhibit the object outside, the professional must use a mixed gilding (attach the gold leaf using a linseed oil drying agent) that will resist climatic conditions for at least 20 years.

Such situations result from technical constraints in each trade or art and are, undoubtedly, numerous. In the event of proceedings in court, the artist may be liable depending on the plaintiffs’ level of knowledge. A professional who commits a fault with respect to a private individual will nearly always be in the wrong. That same professional who commits a fault with respect to another professional in a different field will also be in the wrong. But a professional who strictly complies with specifications produced by a professional architect and historical monuments inspector will not necessarily be guilty, unless it is stated in the specifications that he has a duty to inform the client of all defects or inappropriate treatments that might subsequently call into question the production and protection of the work, as provided in the French standard NF P03-001.

These examples cover the scope of application of the duty to inform that is applied to contemporary and antique art trades: the duty to obtain information, warn and advise.

The activity that primarily interests us in this Review is clearly the expert evaluation of works of art, whether this be the expert’s primary or incidental activity.

The expert being obviously an excellent technician in his discipline, he will have an even greater duty to inform his clients, when carrying out a private expert evaluation, or the parties, when producing a court-ordered expert report, of any significant information that may arise or be already present or if he becomes aware that the work is a fake.

The various obligations should, however, be differentiated depending on whether the procedure is private or court-ordered.

The private expert evaluation

For private expert evaluations requested by a client, the expert has the same duties to advise and inform as any other service provider: when he discovers a defect or any information that proves that it is a fake or any significant damage, he must inform his client, even if that is not the purpose of his task. This situation, which arises relatively often, then leads to the presentation of a remedy. Where his task relates to authenticity, he must advise his client on the research that should be carried out in order to determine such authenticity and the scientific means, ie, the examinations and analyses, that will be appropriate in unearthing the truth.

Experience helps the expert apply his duty to inform and reassure the client.

There are so many examples that I will choose only the most significant.

When listing an important collection of the works of Diego Giacometti (1902/1985), I straightaway remarked (from only having briefly glanced at the patinas) that there might doubts over two works. Initiating further investigations into them, I did a comparative evaluation that confirmed the grounds for my doubt and I informed the owner of the collection and the rights-holder of the artist (an Alberto and Diego Giacometti chessboard for Jacques Adnet, c. 1947). The collector, who had just learnt that he had lost several hundreds of thousands of euro, politely thanked me and withdrew the fakes from his collection.

Then, several years later, after the dispersion of the collection and when carrying out a more in-depth evaluation, I realised that two other works were also fakes and that they came from a foundry the activities of which had stopped following court convictions for unlawful copying by an organised gang. Having been instructed at the time by the public prosecutor to separate the wheat from the chaff amongst the seized bronzes, I was able to draw parallels and inform the collector and the rights-holder of their origin, providing the relevant evidence.

These two examples highlight the duty that a professional has to inform his client even if he risks annoying him…

Does the fortuitous discovery of fakes held by a dealer or auctioneer automatically lead to the application of the duty to inform? First, who should be informed? The seller? He may be the counterfeiter or his accomplice and warning him that he has been found out will not help prevent counterfeiting, as he may then simply refine his technique or attempt to reduce the indelicate expert to silence. It may be that he is already the subject of a preliminary investigation by a public prosecutor and the intrepid expert may be in the way of specialised investigators.

If the expert considers that his discovery is important, he must inform either the rights-holders or the central office for the prevention of trafficking in cultural objects that is situated in Nanterre. Thus satisfying his duty to inform, the expert will be interviewed and the public prosecutor or the police officer will decide what is to happen next. If a preliminary investigation is initiated, the informer expert can no longer be appointed to carry out an expert report, as the essential principle of fair process must be applied.

Depending on the importance of the discovery, a breach of the duty to inform may be alleged by a prosecutor, who will then convoke the expert.

For example, after having participated in a television programme on the counterfeiting of works of art (Capital), an expert, well-known for his court-ordered expert reports and who had assisted journalists, was convoked by the prosecutor and the Nanterre service for the prevention of trafficking in cultural objects. When passing through the Saint Ouen flea market with a hidden camera, he had discovered a bronze that was similar to Rodin’s The Age of Bronze. This shoddy replica, which had been bought by the television production company and presented during the programme, had raised concerns with the service.

After questioning the expert, the investigators, reassured by the poor quality of the fake, and with the Rodin Museum (the rights-holder) not wishing to become a civil party, the file was closed without any further action being taken and the expert ‘discharged’ after having failed, according to the prosecutor, to satisfy his duty to inform.

In all of such transactions, where there is a significant doubt over the authenticity of an object, the seller has a duty to inform the buyer. Otherwise, in the event of any subsequent dispute, there may be a demand for cancellation of the sale with accompanying proceedings for damages and interest and a claim under the current case law and Arts2. L.321-17 of the Commercial Code3 against the professional or non-professional seller or the assisting expert.

An expert who is instructed by a private individual or a professional must also inform his client of all investigations that may be necessary to uncover the truth: condition, authenticity, veracity of the certificate… Where a fact is proven, the client must be informed. For example, it is well-known among experts that from the death of the French sculptor César in 1998, more than 90% of the certificates produced by his companion or various defrauders relate to fakes (P v. MP, Grasse Regional Criminal Court, judgment of 25.01.2010). The court-appointed experts in the case even estimated that between 3,000 and 5,000 fakes have not yet been found.

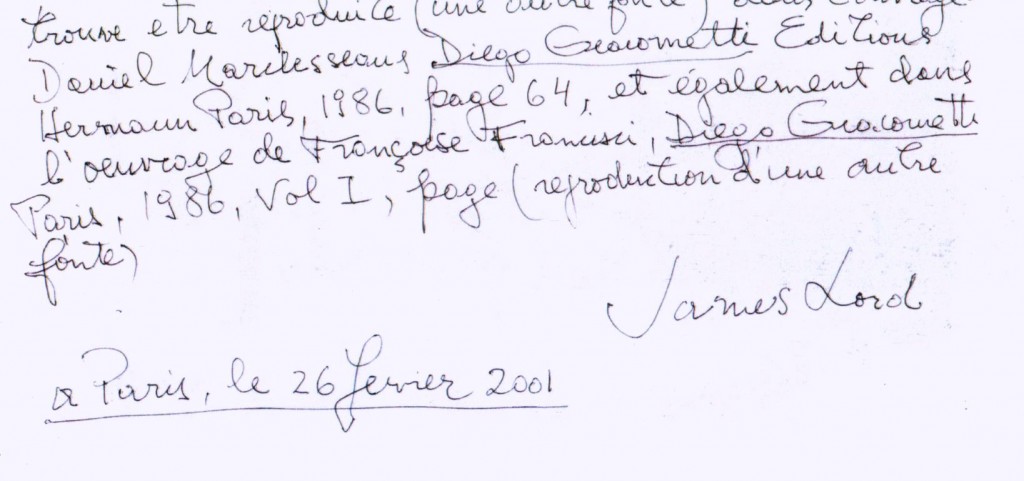

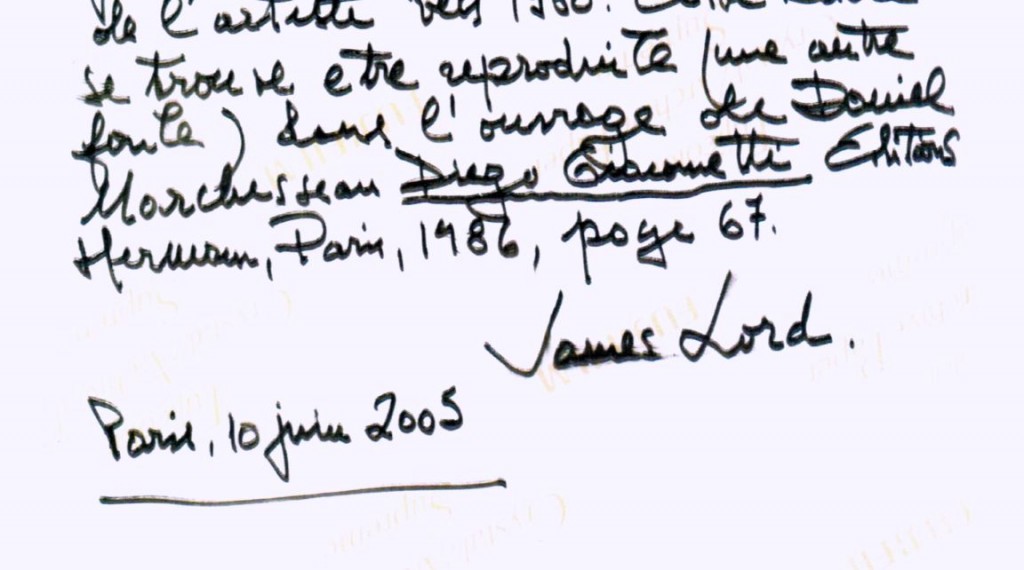

Another court case: only one in two of the certificates produced by James Lord (1922/2009) for the works of Diego Giacometti are reliable and only those after 2000, as a ‘particularly unscrupulous’ expert produced and signed them without his knowledge (T-B v. R. de C., Paris Regional Court).

In the event of a subsequent dispute, the expert may be liable if he did not propose all investigations necessary to find the truth4.

The court-ordered expert report

The same discoveries made during a court-ordered expert report, whether civil, criminal or administrative, will not systematically lead to the same obligation to inform.

First, it should be remembered that the expert must fulfil the task defined by the judge and not, in principle, reply to other questions or initiate a widening of the scope of his task.

In criminal cases, he must first inform the judge, the public prosecutor or the police officer who instructed him so that such person can issue an order widening his task or commence supplementary proceedings. In which case, he will send a written estimation of his additional fees and must wait for approval.

In civil cases, if the parties unanimously agree, he can include such information in his report. Otherwise, the party who wants such formal inclusion applies to a court or, in default, includes it in his summary submission, thus obliging the expert to include it in his report.

In conclusion, the art world does not escape application of the duty to inform and advise, whether it is in relation to the trading in ancient works of art or those produced by artists who are still alive or in specialist assessments, ie, that of expert reports.

There is increasing case law on this duty, thus forcing professionals in the art market to inform and advise their clients.

NOTE

(1) Article L.111-1 amended by Art. 35I of Law 2010-853 of 23 July 2010: All professional sellers of goods must, before entering into a contract, ensure that the consumer is able to understand what the essential features of the item are.

Article L.111-2 amended by Art. 35I of Law 2010-853 of 23 July 2010: All professional providers of services must, before entering into a contract and, in any event where the contract is not in writing, ensure, before the provision of the services, that the consumer is able to understand what the essential features of the services are.

(2) Cass. 1st Civ., 16 May 2013, no. 11-14.434, in which the Court of Cassation ruled on the issue of the liability of an owner who had offered a work of art for sale the authenticity of which was in doubt.

(3) Article L.321-17 of the said Code provides that: “companies organising the sales of items of personal property at public auctions, public officers or prosecutors who have competency to carry out court-ordered and voluntary sales and experts who carry out valuations of the goods may be liable, under the regulations applicable to such sales, during or at the time of the public auctioning of such goods”.

(4) (fake A. Rodin bronze) Paris Regional Court, 1st Ch., 1st Sect., 14 March 1996, Juris-Data no. 042912), painting by Thomas de Keyser (Versailles CA, 1st Ch., Sect. A, 15 May 1997, Juris-Data no. 044179).