On 9 February 2011 at Sotheby’s in London, a 75 cm plaster copy of the very famous Eve by August Rodin set the bidding on fire at £260,000 (€308,750). Six weeks later, at an art fair in Maastricht (the European Fine Art Foundation), a famous English art dealer reluctantly agreed to sell it for $2,000,000 (€1,420,000). Asking him what justified such a price, he answered that it was the original plaster from the master artist at the origin of all of the bronzes of this model! As such “it is priceless…” he stressed, accentuating the last syllable. Astonished, I took a step back and looked at his business sign… Ah! I was reassured: he was a dealer in paintings…

“So what do you think? Beautiful, isn’t it?” he said. “Absolutely. But what makes you think that it is the original plaster?” I asked. His face lit up, touched by grace, as if Eve in person had appeared before him, answering: “Its beauty!” Unfortunately, love is sometimes blind… It was only a workshop plaster covered with a protective layer of shellac, several copies of which had been produced. This one contained metallic inserts ready for the cross of a pointing machine that is used in order to create an enlargement or a copy in marble. It also had scars from the creation of several moulds used to pour bronze casts using the sand casting process.

I said nothing, but I must have been smirking because he broke the silence, saying: “The cost is forgotten but the quality remains”. Sure, but we should, at the least, buy what we think we are buying and not a derivative product! I replied that he was wrong and that it was a workshop plaster. His cheeks deflated, he frowned for a second, then, taking a deep breath, he concluded, smiling: “It’s my baby, for me it will always be unique…”. The discussion ended and he turned to speak to a client…

This anecdote reveals the extent to which current art market is unfamiliar with ancient and modern techniques in marble or bronze statues, something I have realized during counterfeiting trials where the various steps required to create a sculpture must be constantly explained to judges, museum curators and rights-holders in order to precisely identify the preparatory copies in wax, clay, Plastiline, plaster, etc.

For the same work, the original plaster is at the top of the value pyramid. Then come the plasters produced during the author’s lifetime, then workshop plasters (which are only tools for the creation of bronzes using the sand casting technique). To which are added plasters that have a purely technical interest and support plasters (thrown into the casts). At the bottom of the scale of values are the modern plaster copies for commercial distribution in unlimited numbers, such as the copies sold by the National Museums Association in museum gift shops, airports and stores. The latter should strictly comply with French law by visibly and indelibly applying the label ‘copy’ and other legal notices (copyright, artist’s signature) but, unfortunately and strangely, this is not always the case. At the bottom of the list are the plasters produced by counterfeiters and con artists by over-moulding the above plasters or bronzes or even works that are copied or invented.

Original plasters that were seized in Germany but are counterfeits sculpted by a forger of Alberto Giacometti’s works. Stuttgart Regional Court, 2010.

The range is extensive. Only a good professional can tell: he will fully understand this essential pyramidal structure because it determines the scale of prices. These can go from several dozen euro for a recent commercial edition to several hundreds of thousands of euro for the original plaster of the same model.

Surface examination of a plaster work (Eve on a circular base, size 1, Auguste Rodin) to detect the exact nature of the originality and uniqueness of this work of art.

Rodin

The legislator has not always distinguished between original plasters and production and workshop plasters. When created during the artist’s lifetime, art historians and dealers call them ‘genuine plasters’. When Eugène Rudier, Rodin’s official founder since 1913, died in 1952, his nephew Georges Rudier recovered ‘the tools’, the workshop plasters, the ‘Alexis Rudier’ trademark and the A. Rodin seal (printed inside the core of the bronzes) for most of the moulds (as they were held by the Rodin museum in the Villa des Brillants in Meudon). He hired his uncle’s workers and the Rodin museum entrusted him exclusively with its production until 1982.

When a workshop plaster became worn out, Georges Rudier requested another from the museum, which instructed a moulder in Meudon to reproduce the workshop plaster using original moulds. Worn-out plasters were ‘officially’ destroyed or sent back to the museum. Unfortunately, these actions were not always registered in either a directory or otherwise.

From several court cases1, we have already seen that the Georges Rudier foundry did not return numerous workshop plasters back to the Rodin museum.

However, that professional must have been aware of clear case law going back to the 19th century on models entrusted by sculptors to founders and moulders: the artist (or his rights-holder) remains the owner of his copyright and his medium. This therefore applies to these plasters, which are used in the workshop to create bronzes and which cannot be either given away or sold without explicit agreement from the artist or his rights-holder. Several artists had given plasters to founders as payment or to thank them, but certainly not August Rodin. In addition, for sand casting, the plaster models are cut into several pieces and stuck back together and, therefore, are easily recognizable.

It seems important that judges, art lovers, experts and historians understand the fundamental differences that exist between an original plaster, a distribution plaster (for multiple production), a workshop plaster, a plaster from over-moulding another workshop plaster or a bronze copy.

The original plaster

Bas-relief, Meilleur Ouvrier de France competition in 1979, original plaster fully removed from the mould, covered with two coats of shellac varnish. Source: Gilles Perrault, Sculptures sur bois, Ed. Vial, Dourdan 1991

It comes directly from the first plaster mould, itself based on an initial model produced by the artist in clay or wax. It is unique because the plaster mould that it comes from, called ‘a hollow cast’, is broken up in order to release it from its negative imprint. It is recognizable by the fragments of clay or wax that remain on its surface and the marks left when removing it from the hollow-cast mould.

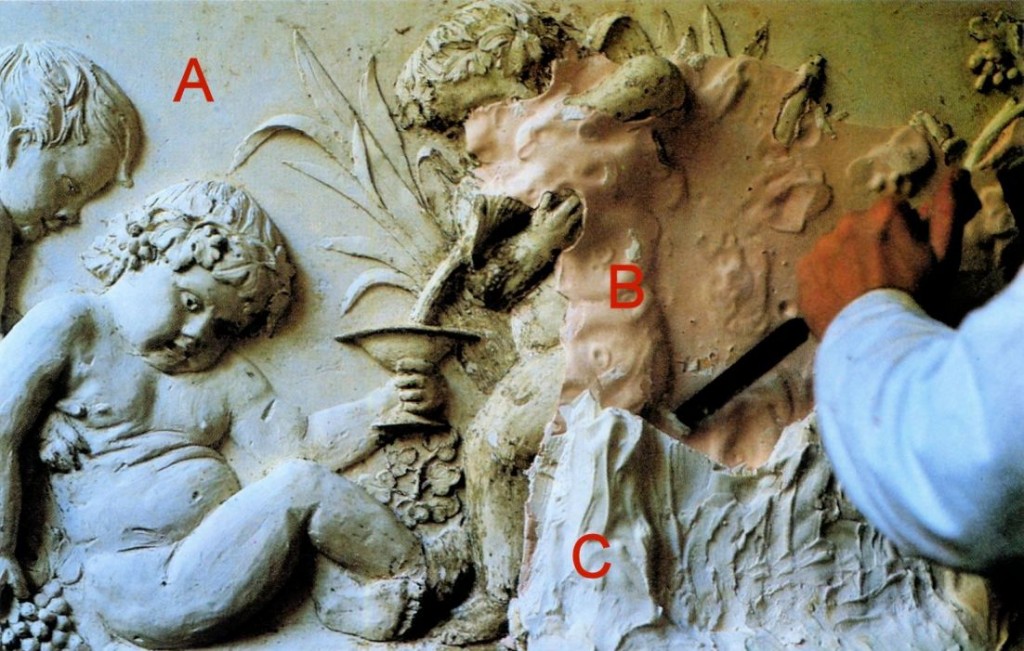

View of the inside of the hollow cast.

Moulding of the copy, positioning of oakum pads to strengthen the edges.

Removal of the original plaster (A) by removing the hollow cast (B and C).

Removal of the original plaster (A) by removing the hollow cast (B and C).

A: original plaster

B: fine plaster in the hollow cast

C: supporting shell of the hollow cast

Full sculpture from the Ecole Boulle, circa 1973. Original plaster bearing many stigmas.

A: macroscopic fragments of clay

B: macroscopic fragments of fine plaster.

C: tool marks left when hollow cast removed

The original plaster is of paramount importance for the artist as it reproduces all the details of the initial work, which cannot be indefinitely preserved due to its initial material being clay or wax. At this stage, it is the sole representation of the work, being permanent but fragile.

A second mould is always made from an original plaster in order to produce copies (in plaster or wax) using the lost-wax casting technique. In Auguste Rodin’s era, these second moulds, called ‘piece moulds’, were made either with plaster pieces in order to remove it from the mould without breaking it and its model or in gelatin in plaster shells. Unfortunately this latter technique was very fragile, deforming the initial work after several copies and becoming rapidly damaged.

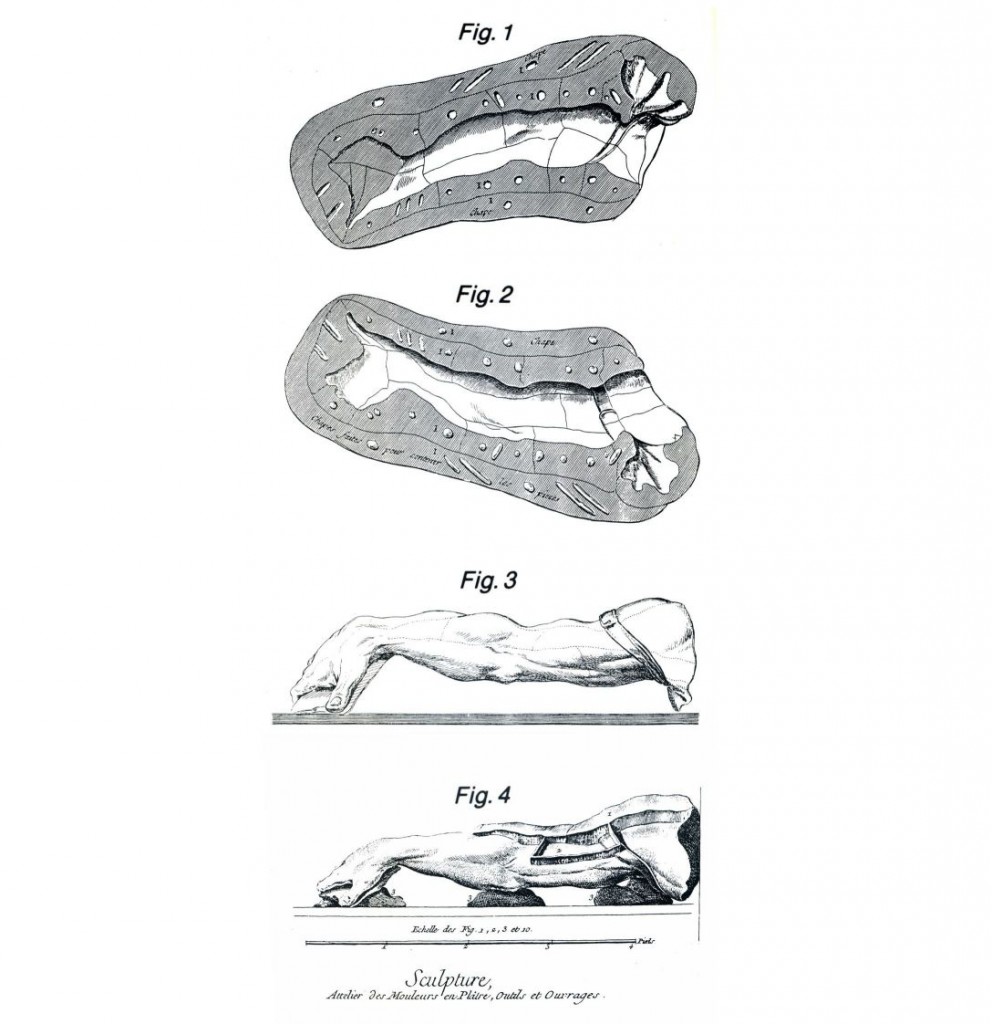

Fig. 1 and 2: multiple-pieces plaster mould

Fig. 3: workshop plaster

Fig. 4: creation of the multiple-pieces plaster mould

Source: Encyclopédie Diderot et d’Alembert

The most accurate, reliable and durable impression was that using the plaster pieces. It was also the most costly and time-consuming. Due to their complexity, multiple-piece plaster moulds were the privilege of professionals who went on request to the sculptors once the clay work had been completed.

We are talking here about the past: in the 1960s and in less than a decade, supple casts in elastomer resin totally replaced previous techniques. The execution speed and the facility of creating such moulds, together with the accuracy of the impressions produced, created numerous vocations for counterfeiters.

The workshop plaster

Workshop plaster copies, made from multiple-pieces plaster moulds up until the 1960s, are easily recognizable. They carry the trace of the joints between the pieces of the mould, also called ‘seams’. Auguste Rodin ensured these were not removed so as to not risk modifying the surrounding volumes. This network of lines very frequently covers bodies and faces and is an integral part of his works. Joint marks can be also be found on bronze copies, which enables the identification of the master model when the bronze is compared with the various workshop plasters. Depending on the positioning of the pieces of the mould, the seams follow the same network and are similar but never strictly identical between two reassemblies of the pieces.

Apollo’s Head, Antoine Bourdelle

To claim that professionals do not notice these marks and any marks from wear and tear on the second mould of a workshop plaster used for bronze editions (using the sand casting technique) or the creation of a distribution plaster, is the falsehood of a Philistine.

The scratches that are visible on workshop plasters are the marks left by metal spatulas during the creation of the sand pieces using the sand casting technique.

Their number precisely indicates the number of sand moulds used for the plaster, including the editions produced in bronze. This and other information helps in the expert identification of a plaster copy. But should the court-appointed expert reveal all of his knowledge in order to respect the adversarial process, at the risk of informing counterfeiters and helping them perfect their work? An issue we may discuss in future articles.

Detail of ‘scratches’, being grooves left by spatulas during the creation of sand-cast pieces (sand casting technique) on this workshop plaster the surface of which is consolidated by applying a shellac varnish.

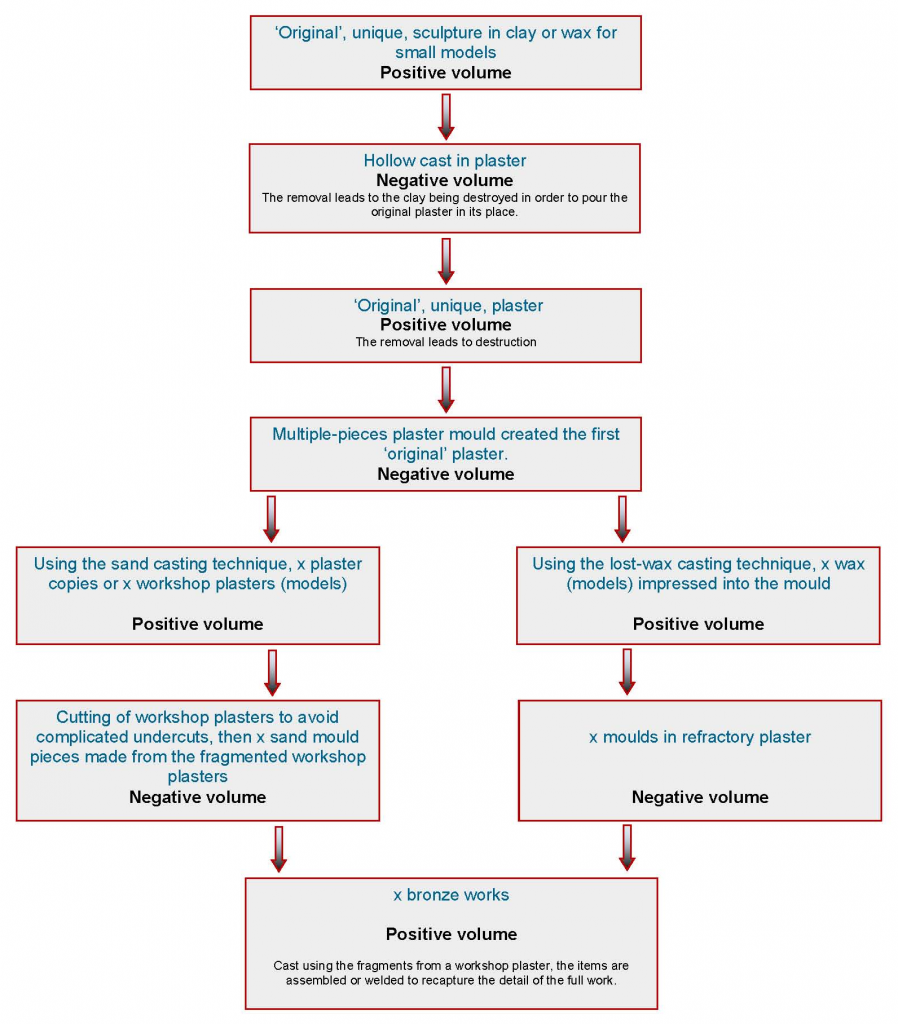

Diagram showing successive stages of the creation of a plaster work up until 1960/1965

Note

1 Including: those brought against Mr G.H. in the Besançon Court of Appeal; the Dijon Court of Appeal case V v. G.H; a case heard on 26 November 2009 in the Créteil Regional Court, currently under appeal and; very recently, in the G.S./G.M. v. Public prosecutor and Rodin Museum case, a judgment of the Paris Regional Court of 21 Nov. 2014.

Article from the Revue Experts no. 118 of February 2015.