All that glitters is not gold… Gilding is the application of gold to wood, metal, glass or ceramic. Frauds are numerous and a purchaser should be extremely prudent when buying, hence the interest of this article…

Revue Experts n°1 – 03/1988 © Revue Experts

Gold has fascinated since the beginning of human kind. Its glitter under sunlight never tarnishes, it is unalterable when exposed to air, resistant to all acids (except aqua regia); it appears to defy both man and time.

Its exceptional qualities, allied with its astonishing ductility (ability to be drawn out into a thin wire) gives it a place of honour in the hierarchy of metals and, more specifically, consecrates is use for gods and heros.

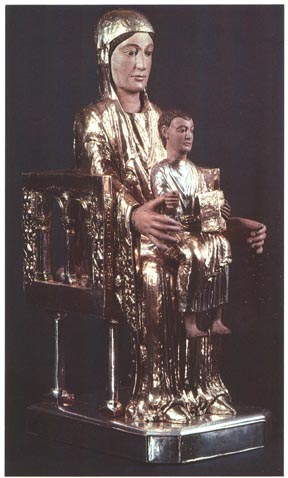

There are unlimited examples of its mystical attraction, from King Salomon, who covered the panelling in the Jerusalem Temple with gold leaf, to the pharaohs who used it for therapeutic purposes and the Greeks and Romans who covered their idols with it.

Even the church could not resist, despite the numerous interventions by iconoclasts, the symbolism and power that it reflected galvanising the faithful.

Closer to home, Louis XIV, whose major preoccupation was to affirm his sovereignty, abundantly used the precious metal to assert his power: he covered furniture, panelling, railings and even roofs of his palace in Versailles with gold leaf. The apartments that constantly reflected the divine being, forming a temple of light, from which the Sun King ruled the world…

I – All that glitters is not gold

Times have changed. The art lover and the professional are frequently confronted with fraudulent gold leafing.

Since the fall of the Ancien Régime, it became widely practiced as the abolition of guild rules permitting the use of lesser noble metals to imitate gold, such as silver or tin, which were subsequently covered with a yellow varnish, or copper.

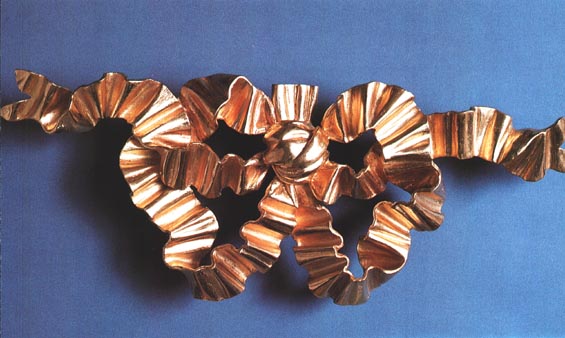

The public authorities, the vigilance of which appears to have essentially focussed on trading in solid gold and silver and their immediate derivatives such as sheets of gold, remained powerless to carry out the inspections necessary for wooden objects covered with gold. In their defense, it should be admitted that 12 m2 of gold leaf weighs only one gramme!… (The thickness of leaves currently used is, on average, 4 microns for single sheets and 8 microns for double sheets). The gold ribbon in the photograph below, which measures a total of 30 cm, is thus covered in less than one-quarter of a gramme of gold, which, for the tax department, is insignificant.

This mathematical reasoning partly explains the lack of interest that the fraud control services have in gilded wood and why numerous antique dealers of modern copies claim with impunity that their items are covered with gold leaf.

On sale nowadays in hardware stores are even “gilding creams for the artistic restoration of gold frames, mirrors, mantels, consoles and chairs”, the nuances of which are pompously called “Versailles Trianon” followed by the qualifying “gold leaf with red reflection”. The manufacturers of such products, who could be the subject of court claims, should be more reserved as the metal powder that is mixed into the cream is merely copper or aluminium!

So how is it that there is such decadence amidst the general indifference? A answer to this question may be found in the lack of understanding of the art of gilding. In France, there is only one school that is supervised by the State, in Paris, that teaches apprentices the art of gilding wood. Five or six gilders per year sit the Certificate of Professional Aptitude after three years apprenticeship.

The artisans isolate themselves and their secrets, erecting a wall between professionals and the media, which they are wary of out of fear of losing their prerogatives. This mutism, associated with a lack of bibliographic material – the most recent treaty on gilding wood dates back to 1886, Editions Roret, Paris – engenders a generalised lack of knowledge by art lovers and facilitates numerous frauds and counterfeits.

Emboldened by such ignorance, the audacious profit from the opportunity by playing on words and offering labels with descriptions such as ‘gold leafing’ or ‘hand gilded’. The confident customer thinks he is buying an object that has gold-leaf gilding and it won’t be the seller who dissuades him. When he realises he has been duped, he will not be able to make any claims as the label does not contain any statements on the nature of the metal used.

Neither do antique dealers or auction houses provide any clarifications as to the nature of the gilding and whether the object has had gold leafing applied with water or a gilding paste or whether bronzine has been used.

It is not rare to find gilded wood with the original water-applied gilding covered with a gilding applied using a gilding paste and a standard layer of bronzine. Auctionneers should use the services of specialised experts more often in order for their customers to gain in confidence, as they may have reason to be surprised to see the same person examining a Louis XV commode, a 17th century solid silver chandelier or a tapestry from Flanders!

What are ‘gilding on wood’, ‘the base’, ‘the preparation’?

A test that we carried out leads us to believe that at least 8 out of 10 owners of gilded wooden objects do not know the answers and were the prey of defrauders.

When Mr B. Peckels, the president of this review, asked me if I wanted to write an article in its first edition, the subject seemed self-evident: inform our readers of the frauds occurring within my artistic specialisation. In the knowledge that our colleagues, and the judges that read these pages, are nearly all if not art lovers at least constantly curious to learn, we considered that some instruction on the traditional techniques of gilding would be useful and interesting.

II – Gilding techniques

Gilding is the application of gold to wood, metal, glass or ceramic. It is also, by way of extension, the application of copper or another metal that imitates gold, for example, a silver layer covered with a yellow varnish.

The basic techniques should be explained first in order to get to the heart of the problem.

1 – Gilding metal

The five processes used for gilding metal objects, whether in copper, tin or bronze, are gilding:

– using mercury,

– by electrolysis,

– using a gilding paste,

– by friction,

– in a vacuum,

– using a varnish.

– Gilding using mercury

The metal object is covered with an amalgam, a mixture of mercury and molten gold, and then heated to evaporate the mercury until it has completely disappeared. After being cooled, the deposited gold is burnished to obtain shiny surface. The burnishing highlights the forms and details that the monochrome gold tone unified.

Unfortunately, this technique is excessively dangerous for man and nowadays only business owners are authorised to apply it, at their own risk. It should be remembered that in the era of the Sun King, when Versailles glittered under all of its gold, dozens of gilders suffering from fevers and mercury poisoning were everyday covered up to the chest in order to gild bronze furniture using mercury. They died swiftly under atrocious pain, sacrificing themselves for a fabulous wage.

– Gilding by electrolysis

Gilding by electrolytic deposit, which appeared in the second half of the 19th century, has today dethroned the preceding process. More economic too, as the amount of gold deposited can be extremely minimal. This method is commonly used for jewellery, faucets or ‘gold-plated’ bronze furniture.

The object being gilded is attached to a negative terminal and placed in a tank filled with a liquid, the electrolyte. The metal being applied, gold, is connected to a positive terminal and also plunged into the tank. When the electrodes are connected, the gold is depositing onto the bronze. This purely chemical gilding has a more reddish colour and is more uniform than gilding using mercury, but has an excellent cost/quality value and can be used on an industrial scale. As the quality of the gilding relies almost exclusively on the quantity of the gold deposited, it is important to determine the thickness before buying an object. Depending on the nature of the object, it can be between 5 and 15 microns.

– Gilding using a gilding paste

The three preceding processes cannot be used for large or immovable objects such as a dome or railings. The gold used is thus in the form of sheets of 7 to 9 cm2, 4 to 10 microns thick, glued using linseed oil dried at 150°C in the presence of a metallic salt (manganese, lead) after having cleaned and isolated the surfaces being gilded. When in contact with air, the oil oxidises, becomes enmeshed and slightly sticky after 3, 6, 12 or 24 hours depending on how it was prepared. It is then said to be ‘in love’ and can receive the gold leaf.

This gilding process offers a brilliance without any nuances but the adhesion of the leaves remains fragile: they do not resist scraping, which is why it is used mainly for architectural items that are out of the range of any shocks or scratches.

– Gilding by friction and in a vacuum

This unsophisticated process consists of scraping a gold nugget onto a hot metal. The deposit that is incrusted into the surface has a variable but satisfactory thickness.

This technique was commonly used in ancient times before the use of mercury supplanted it.

Gilding by way of projection in a vacuum is a modern process that is, in particular, used to apply small deposits, such as on the visors of astronauts or firemen to reflect the sun’s rays, for the first, and heat for the second. The thickness of the gilding deposited on the visor is less than one micron.

– Gilding using a varnish

Gilding using a varnish is commonly used since it was recommended by Louis XV to save the quantity of gold that his subjects used on bronzes.

It is in fact a yellow varnish that is applied on heated pewter. The effect can be misleading but it does not resist the passing of time. The varnish cracks and the metal ends up oxidizing.

2- The gilding of glass or ceramic objects

– Gilding by way of fusion

The most commonly used gilding for glass or ceramic objects is gilding by way of fusion. The gold leaf is placed on the glass or ceramic and the temperature raised below the point of fusion for the object but sufficiently high to melt the gold stuck to it.

– Gilding using a gilding paste

A second technique exists for glass that has been used since antiquity and that developed, in particular, in the Bohemian period in the 17th to 19th centuries. The “zwischengoldglas”, being one glass inside another, are very much sought after due to their rarity. The exterior of the glass object that is on the inside is covered with gold leaf attached using a glue mixture. The gold leaf is then engraved with a decorative design then the glass is inserted into an external glass envelope and welded using heat (see photo).

|

|

3 – The gilding of stone and marble objects

The gilding of stone or marble objects is not recent but was commonly used to gild sculptures of Egyptian or Greeks religious edifices. The gold was applied in the form of gold leaf using a gilding paste with a slight difference to the preceding techniques in that the porosity of the object needed to be insulated using a varnish (shellac). Gilding by way of friction was also used to cover hard and porous stone.

4 – Gilding wood

The preparation of primers:

Wood is one of the organic materials that reacts the most to hygroscopic variations: it increases in volume when the surrounding air becomes humid and retracts when the air is dry.

It also has the particularity of having a varied amount of grain, depending on the type of wood. Gold leaf placed directly onto bare wood highlights the grain, which considerably enhances the perception of volumes and counters the effect sought, being that of imitating solid gold.

In ancient times, therefore, an intermediary layer was applied between the wood and the gold leaf, masking the surface aspects and diminishing the dimensional variations due to humidity. This buffer layer contained a mineral (finely crushed limestone), a binding agent (rabbit skin glue) and a solvent (water). Since the 16th century, rabbit skin glue has been replaced with sheepskin glue.

The coating, from the Middle Ages called a primer, is applied at 60°C in 10 to 12 thick layers. Its surface is then smoothed then covered with two very light base layers (kaolinitic clay, which served as a base for the gold, also called bole or Armenian bole) in the areas to be burnished. The kaolinitic clay compresses under the pressure of an agate stone and the gold leaf becomes as smooth and shiny as the surface of a mirror.

|

– Gilding using water

The gold leaf is applied using water to the base, which is a glue on which, in contact with the liquid, regenerates. It can then be covered with a light layer of skin glue (highly diluted in the water): the matt finish. The glue traverses the porous sheets and sticks to the coating. The gold, which is ‘sandwiched’, becomes matt and better resists wear and tear. Brilliance is obtained by rubbing with an agate stone.

The gilder sometimes uses the thickness of the coating to produce engravings or attach small stones (Roman inlays).

This form of gilding, which is the focus of much of our attention, is the only one that was used up to the end of the 18th century for gilded wooden objects that were stored out of harms way. The removal of guild rules had the disastrous consequence of authorising mixed gilding for the same object: gilding paste for the matt areas, water for the brilliant areas.

– Gilding using a gilding paste

The process used to produce the paste (dried linseed oil…) is easier and more rapid that the preceding gilding process. This economically advantageous technique does not offer the same advantages of the matt and brilliant contrasts as gilding using water, as the film of oil flattens out the volumes slightly.

A new paste has been used since the 1970s, being a water-based paste (vinyl resin emulsion in water). It produces a film that is thicker than the oil paste, which is inconvenient because the contours of the metallic surface are less precise, but it remains ‘in love’ for seventy hours, compared to the preceding method, which remains receptive for a maximum of one to two hours.

III – The difference in cost in manufacturing and restoration

Not many people see the difference between quality gilding (using water for wooden objects and mercury for bronzes) and poor quality gilding (using oil, the simplified paste) substitute that bears the pompous title of gilding.

The cost in fabrication and restoration varies from one to twenty between gilding using bronzine (substitute comprised of copper powder diluted in a varnish and applied with a brush) and a gilding using water, for example. It is essential to ask for details from a vendor on the base metal used, its nature, the number of carats of the gold used, the thickness of the gold leaf (single: 4 microns, double: 8 microns, extra-thick: 12 microns…) and the technique used.

Numerous restorers can work on works of art using new products that are as dangerous as they are attractive, such as aluminium or copper powders mixed with wax, which flatten out contours then rapidly darken as they oxidize. The labels for such products, sold as ‘gilding cream’ or ‘Dutch gold’, etc, always omit to specify the nature of the metallic powder or downright mislead the customer by claiming: ‘gold leaf with orange reflection”. Who would be liable for damage to a work of art in court? The dishonest manufacturer or the confident but incompetent user?

IV – The problem of competence

It is remarkable that, in our era, restoration can still be synonymous with damage.

As surprising is the fact that no details on the gilding used are provided by auction houses. There is no information on the quality of the gilding or its nature. Only somewhat laconic terms are used in the catalogues, such as ‘standard restoration’, ‘good condition’, ‘average condition’, an assessment of the cost of restoration being left to the bidder.

This lacuna can have significant consequences, first for the client who, wanting to clean his painting’s frame, discovers the fraud, then the auctioneer who is responsible for the sale and the expert to whom the auctioneer turns.

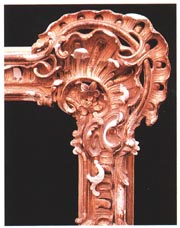

Take, for example, a frame that went up for auction recently. The first photograph is that appearing in the catalogue. The description by the expert gives its measurements, an estimated value and the following title: “Superb wooden frame with sculptured and gilded spandrels and openwork with leafy shell decoration…”. No mention of the state of the wood and the gilding that are undoubtedly considered to be in good condition. However, when the frame was presented for cleaning by a restorer, the new owner discovered with much astonishment that the original gilding had been covered with a gilding paste then bronzine, hiding numerous plaster restorations. The cost of cleaning the bronzine, the gilding paste and the repairs to the restoration work exceeded one-half of the purchase price!

|

|

|

Such cases provide much food for thought, as the expert should have been more precise.

The sin of the omission demonstrates the need to be rigorous and to better inform the art buyer.

A purified market in gilded wooden objects would no longer be so stressful and the market would rise, like that of the market for paintings where even the most minor restoration is announced by the expert.

V – Conclusion

In light of the use of certain labels, it is clear that all that glitters is definitely not gold. We would recommend that you be extremely prudent when undertaking a purchase and, clearly, seek out advice from an expert if possible.

Bronzes gilded using mercury and wooden objects gilded using water have not yet reached their maximum prices and it is, therefore, easy to create a collection at affordable prices, providing the collector has a minimum amount of knowledge and taste.

|

|

To learn more :

Dorure et polychromie sur boisTechniques traditionnelles et modernes

|