The expert, between a rock and a hard place

Expert reports on works of art are often carried out on personal property for the purposes of inheritances, insurance or in relation to fortunes. If private, they are clearly confidential. In civil proceedings, the court expert is bound by proceedings confidentiality, which is even more restrictive in criminal proceedings. Describing these various contexts, Gilles Perrault discusses the delicate position the expert finds himself in, subject to the contradictions and powerlessness imposed by such confidentiality.

Article in the Revue Experts n°112, February 2014 © Revue Expert

By way of introduction, it should be noted that an expert examination of a work of art is confidential even if requested privately by the owner and the work is not the subject of any dispute. Such discretion is necessary for such reports, which are often carried out on personal property, inheritances, for insurance purposes or in relation to a fortune. The ethical rule advocated by all professional associations is the recommendation that the expert retain the utmost discretion in relation to his report, even if it is to be provided to an insurer, the tax department or the heirs.

1. Confidentiality of private reports

The private expert examination of a work of art remains destined for use by only the person who ordered the report or the recipient chosen by the latter and is subject to a contract that defines the limits of the task and often its cost.

It should be remembered that because the expert examination of a work of art is not a regulated profession, the expert is not bound by professional secrecy within the strict meaning of that term but by contractual confidentiality.

An expert who discloses the results of his report without authorisation from the client risks a court case on the grounds that he has not complied with the confidentiality clause.

In the absence of written consent, the expert discloses the results of his investigation only to his client. Even if he realises that the work the subject of the examination is a recent fake, he does not have any duty to communicate that fact to a public prosecutor, the artist or his rights-holders. He cannot, therefore, a priori be held liable or be a handler of illegal goods in a counterfeiting case. The situation will be different, however, if such incidents recur and raises some concerns for him, as his personal liability may become an issue due to his poor judgment. The prosecutor or investigating judge might question him about it and even charge him with complicity if it appears that he was protecting the fraudulent activity by remaining silent about it, with the buyer and the rights-holder applying to join him to their civil proceedings. The activity of carrying out an expert examination of a work of art at the request of a private individual therefore requires a measured confidentiality in certain cases, left to the appreciation of the expert in the event of the discovery of criminal fraud. Obviously, the discovery of an isolated, ancient, fake does not fall within this scenario. To state it simply, the expert may be liable only in the event of a clear, recent, fraud and the mass production of fakes.

______________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________________

2. Expert confidentiality in civil proceedings

An art expert who is appointed by a court in civil proceedings (District Court, Regional Court, Commercial Court, Administrative Court) is bound by proceedings secrecy and cannot disclose information relating to the carrying out of his report or the report itself to any person other than the judge who appointed him and the parties to the proceedings. The parties who receive the report are not bound by the same obligation and sometimes do not hesitate to release it publicly in order to serve their own interests.

The fragility of this shared secrecy in civil proceedings sometimes results in a party not wanting to disclose his documents to his opponent so that probative information (identifying, for example, fakes) is not subsequently known by counterfeiters, which is a situation that is similar to that of industrial secrets and which is dealt with in the same way by the court-appointed expert.

He can examine the confidential documents provided by one party by himself and attest to whether they have a positive or negative result on his task. Without revealing the contents of the documents that he examined, he certifies the existence of any proof, whether in favour of a particular party or otherwise.

For example, the rights-holders of a famous designer who had had furniture seized that was attributed by dealers to their ancestor proposed that the parties prove their opinion by leaving it to the expert to examine the annotated daily notebook of sketches in which the prolific creator had set down his ideas.

Clearly, there was no question of the plaintiff releasing the keys to the artist’s creative work to anyone else. The court-appointed expert therefore alone examined 40 years’ research. The artist’s creative process was kept secret. The expert, appointed pursuant to a court order, is thus caught between a breach of secrecy and the respect for fair procedure. Where one party opposes its document being released to the other parties (idem for manufacturing or commercial secrets, etc), it is preferable that the court-appointed expert apply to the judge for authorisation for only him to access the information contained in the document.

3. Expert confidentiality in criminal cases

In my opinion, this is the confidentiality that is the most restrictive because the expert is, on one hand, bound by the secrecy involved in the investigation and, on the other hand, the secrecy applying to his activity until the judgment is released publicly and no appeals have been filed.

It should be remembered as well that the expert is merely a specialist serving the judge who appoints him and he cannot transform himself into a righter of wrongs when discovering frauds unrelated to the proceedings. For example, when a seizure takes place at the home of the person charged, often the expert discovers other criminal offences (counterfeits) committed by either the person visited or his accomplices. He raises such matters with the police officer who is accompanying him, the prosecutor or investigating judge who ordered the seizure. If the police officer or judge considers that the discovery is outside the scope of the proceedings or that it needlessly risks hindering the proceedings, it is not taken into account. The information discovered, useful for the history of the work of art, remains in the expert’s memory without being disclosed to historians.

In the contrary situation, if the expert has convinced the court of the importance of the finding, the court will commence ancillary proceedings and the object or the proof will be seized, to become the subject of new proceedings.

Ancillary proceedings are rarely commenced, however, for the evident reason that there are already too many cases either the subject of preliminary investigation or in court.

The court-appointed expert is aware and has proof of the existence of fakes that often attain the hundreds of thousands of euro, as authentic works with irreproachable traceability can exceed millions of euro when sold (an authentic 71cm bronze Thinker by Auguste Rodin, cast in numerous examples by counterfeiters, reached €11,600,000 at an auction house in New York last May).

The expert can warn neither the intermediaries (the dealers, auctioneers, auction-house experts) nor the purchasers. He is de facto bound by secrecy and merely notes the fraudulent sales, powerless to warn the parties involved.

Another secrecy constraint when carrying out court-ordered expert reports in criminal proceedings: where a counterfeiting network is discovered, the investigation can last several years (up to 5 to 6 years for cases with overseas ramifications and the trial may take place only after 7 to 8 years). In addition, if the parties appeal to an appeal court then to the highest French court, several more years will pass before the legal truth can be disclosed…

The criminal underworld, aware of the proceedings, has all the time in the world to sell the remainder of the stock that has not been seized. Powerless, the expert can but stand and watch such fraudulent sales without raising any objections publicly.

In conclusion

The ‘risk of human death’ or a breach of public morality is not particularly high in cases involving the counterfeiting of works of art. The expert is not, therefore, systematically released from his obligations of secrecy and confidentiality.

Not being able to voluntarily intervene to defend the property of another person, his acts are confined to findings of fact and not their disclosure. Often, therefore, it is he and he alone who bears the weight of the truth.

_____________________________________________________

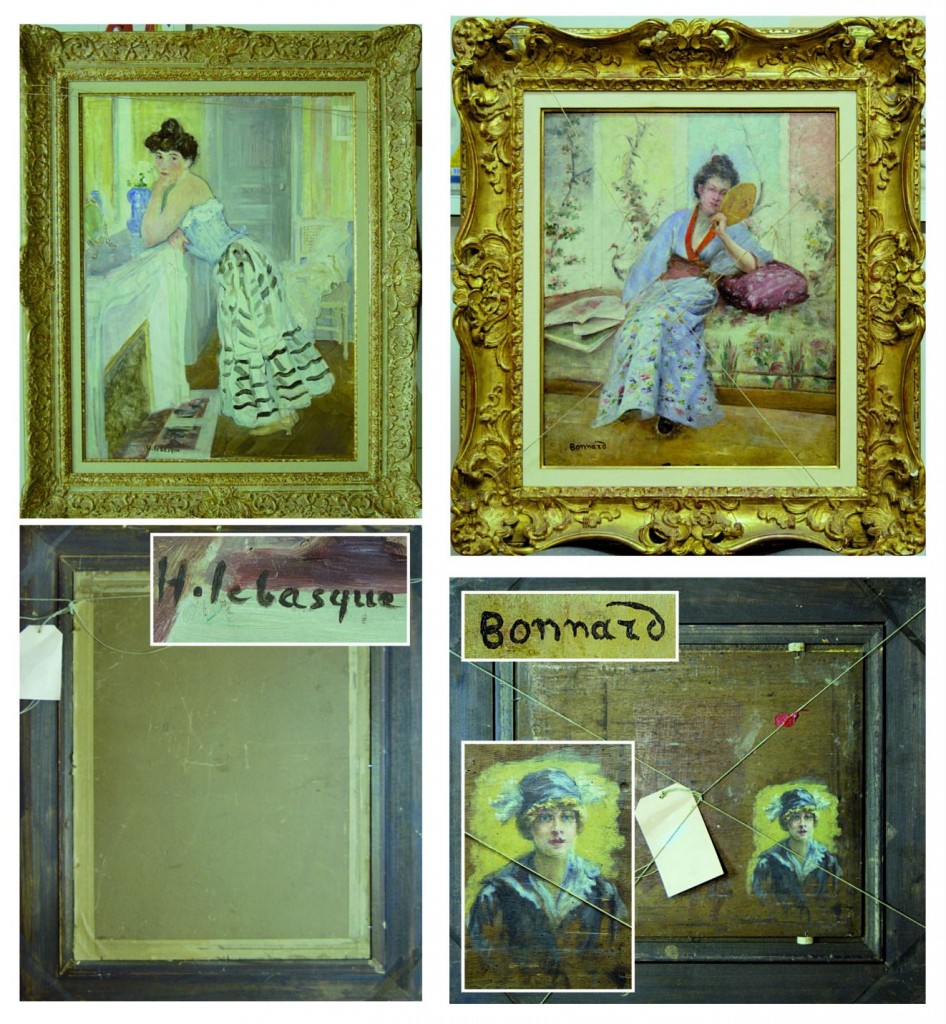

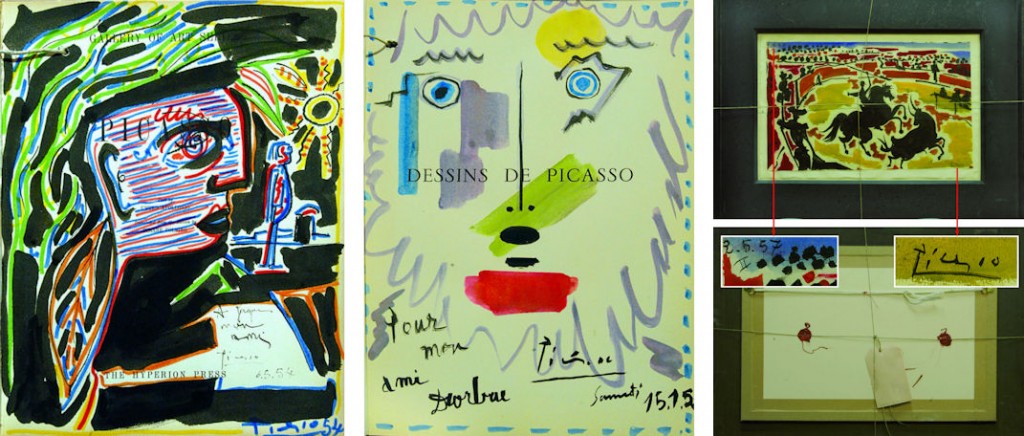

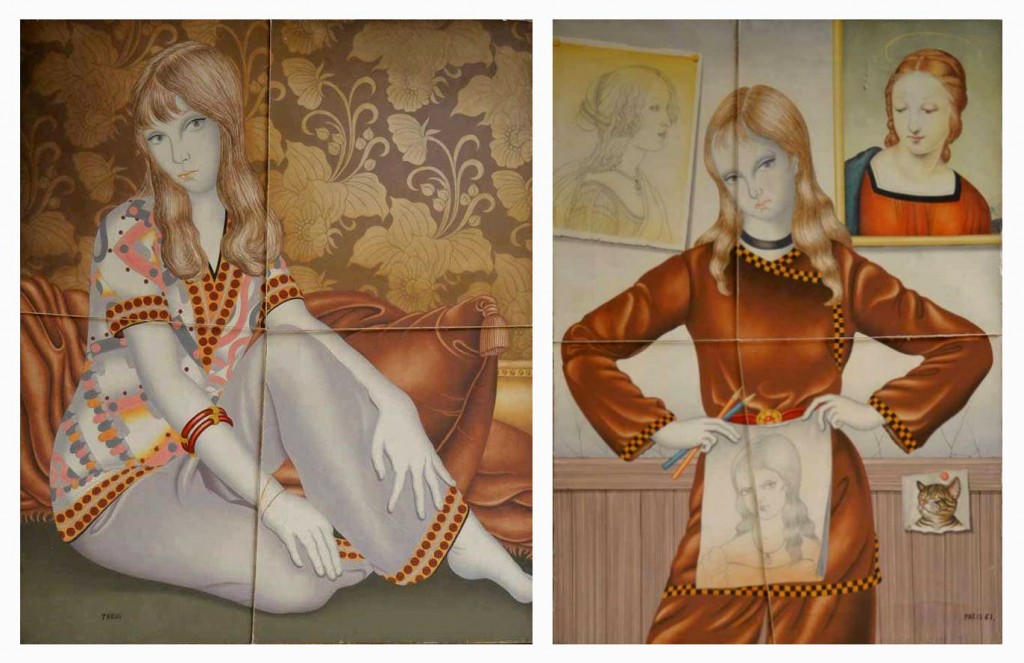

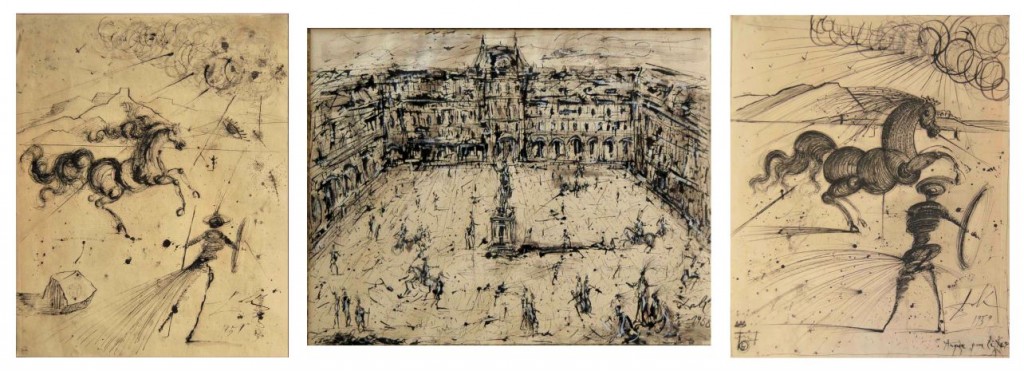

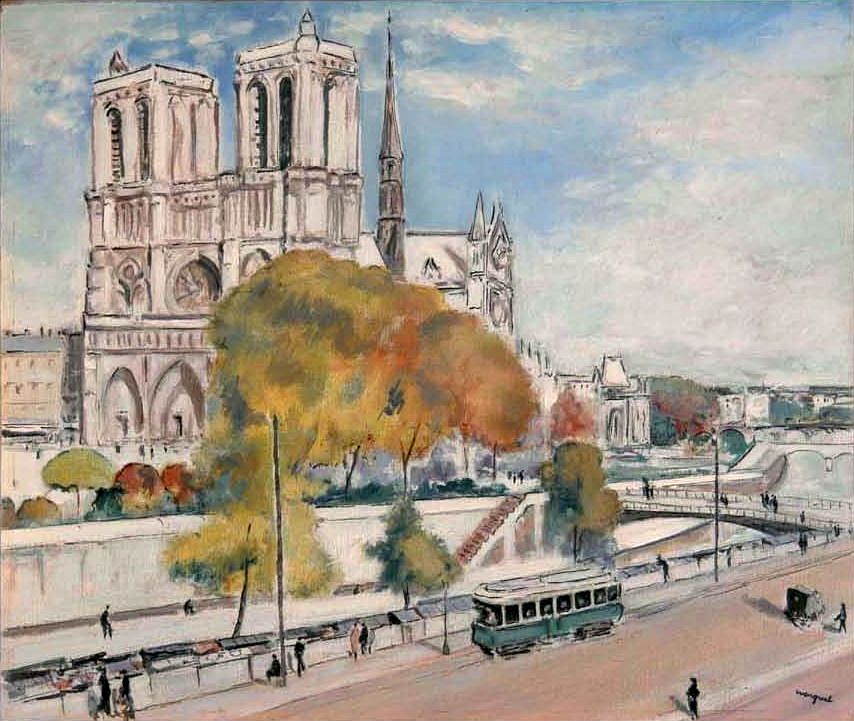

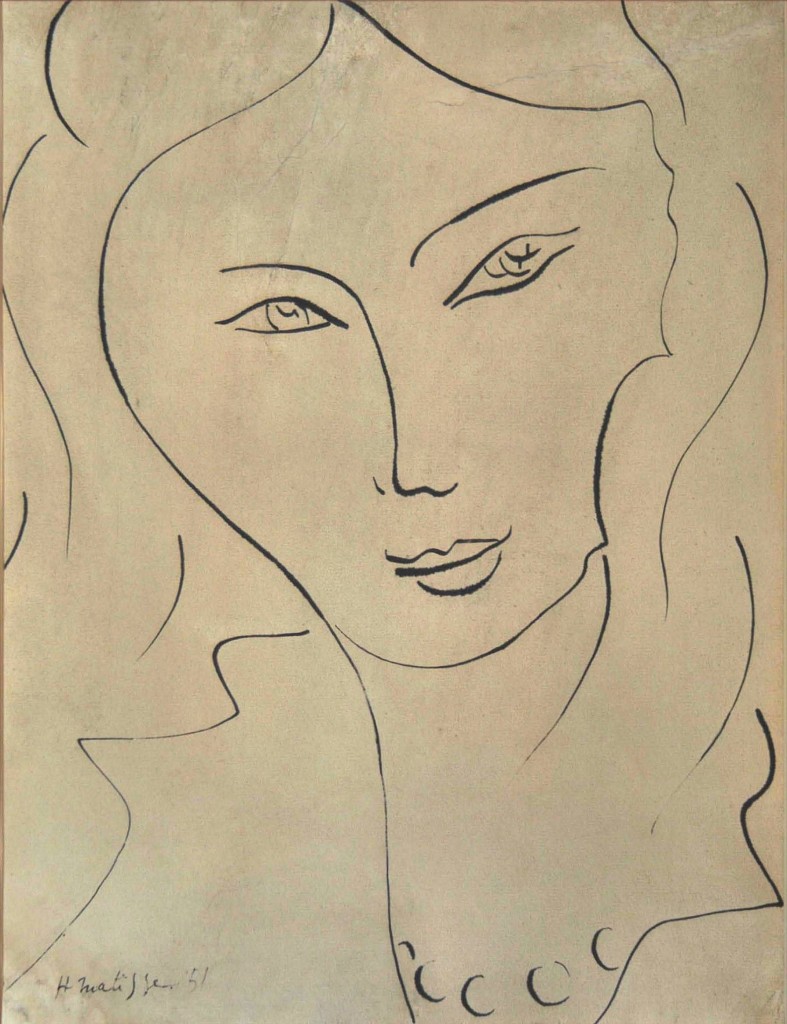

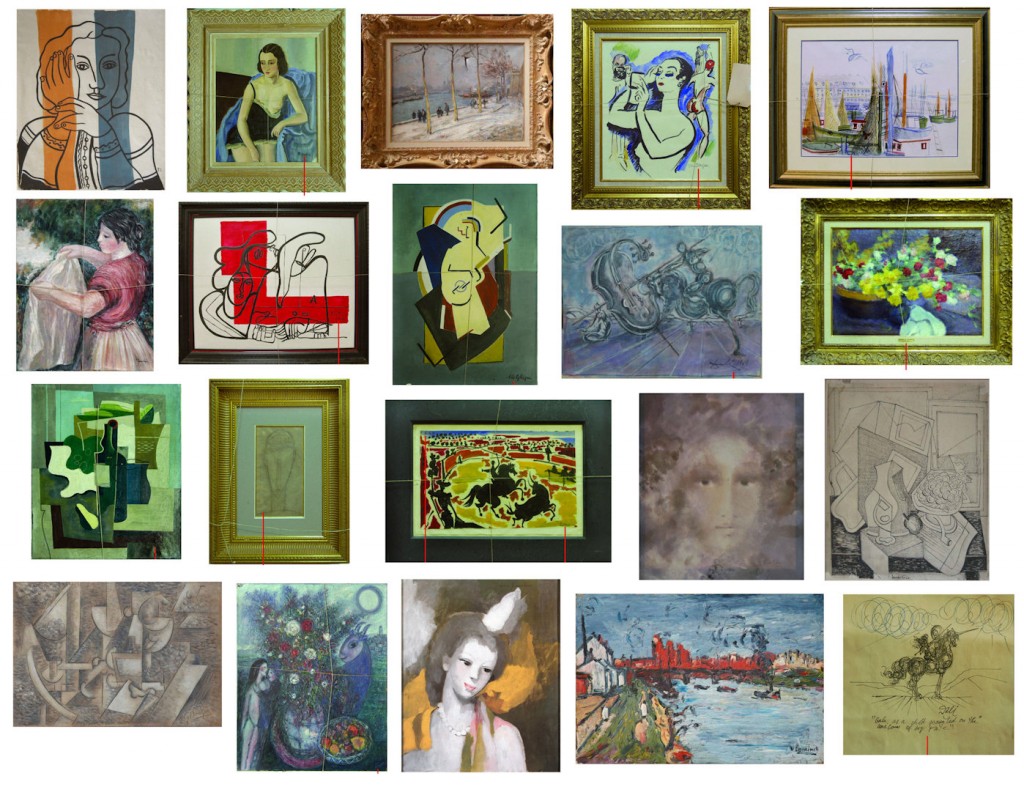

With the case of the counterfeiter of the works of master painters, Guy Ribes, having been decided in 2010 in the Créteil Regional Court, we are now able to disclose which fraudulent works were seized and included in the court proceedings during the investigation phase, including this example. There are still several hundred others that have yet to be found.