Bronzes are part of the French people’s ancestral patrimony. Many families own or have inherited items produced at the time of the great popularity for bronzes at the end of the previous century; museums are overflowing with well-known works and there are numerous, high-quality, art books dealing with famous sculptural artists. France has held and continues to hold a leading role in the world through its artists, foundry owners and its market.

The transmission of estates, the eagerness of collectors and art amateurs, the quality and number of art galleries drives this market. It is extremely important, therefore, that the quality of the objects transferred is recognised. This article aims at showing the crucial role that experts have in this analysis, its complexity and the capacities required for this research, which includes knowledge about the foundry, the engraving, the patina, the artists and the habits of the art world.

La Revue Experts n° 39 – 06/1998 © Revue Experts

By Gilles Perrault, Stéphanie Moncel & Claude France.

THE BIRTH OF A SCULPTURE

The artist, working in a material of his choice, the physical qualities and facility of creation of which he masters, creates his work (wood, stone, marble, plate, plaster, recycled materials, etc).

This work may remain as it is – generally the case for statues in stone, marble, wood, etc – and is presented in its original state. This creation constitutes the ‘original’ work in the true sense of the word.

It is clear, however, that works created out of materials such as marble or stone can also be duplicated either in the same material or in a lesser-quality material: Marly’s Horses, the Provinces in the Place de la Concorde, the Pompey statuettes, which are regularly stolen and, thus, replaced.

These works in stone, marble, etc, can also be reproduced in large quantities, whether in original or smaller size (all of the reproductions presented in the larger museums are predominantly made out of malleable materials containing stone or marble powder).

Bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, is but one duplication material amongst others… It is chosen for the ease with which it is produced, its inalterability and the differing aspects of its beauty produced through natural or artificial patinas…

Bronze, which can only be handled when melted and poured, cannot, under any circumstances, be directly worked by the sculptor. Any bronze statue is, therefore, produced from an ‘original’ work that is created through the artist’s hands and imagination.

THE WORK OF THE FOUNDER, THE ENGRAVER, THE PATINEUR

• The different materials

In using the sculptor’s original, their art consists of faithfully reproducing one or more copies in various materials – alloys of lead, copper, bronze, brass, iron, cast iron, etc – but always by pouring metal or an alloy into a cast (mould or shell), work that involves duplication.

The ‘original work’ or ‘master’ can be used directly to produce the mould or cast into which the metal will be poured. This cast is always the ‘negative’ of the work being reproduced.

The various materials used by sculptors have very different physical qualities, some being able to support the work carried out by the moulder or founder better than others. This original, primary, work may be destroyed and, depending on the moulding process chosen by the founder for the first copy (objects in wax, modeled by the initial artists and destroyed by being incorporated with the wax after it has been covered with a heat-resistant coating to form the cast, a receptacle for the molten metal: single lost-wax process).

• The first replicas

Generally, the sculptor, wanting to retain the integrity of his work that he has produced in a softer material (clay, for example), has either a first reproduction (generally in plaster or a modeling material) produced, which will be given to the founder if it is sufficiently resistant, or a second reproduction, called the ‘workshop plaster’, which will replace the ‘original’ work. The casts produced will, therefore, already be copies of a copy.

It is important to understand that the founder can use either the ‘initial’ work by the artist or a first replica or another bronze known as a ‘master model’, ie, copies of copies, in his ‘reproduction’ work. This successive work is not carried out without altering the initial work, which is the justification used by art enthusiasts who seek the copy that is closest to the initial work and, therefore, the closest to the sculptor’s intended creation.

• Works produced during the life of the artist or posthumously

It is easy to see the interest in having a ‘copy’ produced during the life of the sculpture rather than a posthumous work. At the various stages of the founder’s work, the artist, if he wishes, can monitor and verify that his work is not altered. It should always be this way, as it enables such ‘supervised’ copies to be described as ‘original works’. The engraving and patina works are particularly important at this stage and it is at this stage in the production of a bronze sculpture that the collaboration by foundry workers and the sculptor can provide an exceptional and unique quality to their mutually produced work. Prior to these final phases, the creator can have only an imperfect version of what such ultimate work will produce in bronze form, bronze being a material that enables effects to be added to the clay object worked by the artist.

THE DATING OF BRONZES

There are, currently, no reliable and economical methods that can be used to date metal alloys dating back several decades.

Bronze, being mainly an alloy of copper and tin, also contains a number of other metals or metalloids. All of these elements can be precisely measured and various methods produce values that are qualitative (presence of such elements) or quantitative (more or less precise measurements of such elements).

The issue is to know if the analysis of the detailed composition of a bronze can accurately describe it and if, through the range of its various components, its date and the identity of the founder can be obtained.

If the resulting elements appear having a significant value, for example greater than 1%, a founder can be relied on to reproduce such formula without difficulty for his customers. Rapid, modern, measuring techniques enable the composition of liquid metal to be determined and the carrying out the requisite identity research before casting either at the foundry or refinery (spectrometric analysis).

An analysis of a bronze cannot, by itself, provide proof of the date.

It is a recognized truth that modern technicians are now able to reproduce objects that contain all the qualities of antique works. To doubt such claim would be to deny the capacities of contemporary sculptors and founders.

Based on inherited traditions and sophisticated technical resources, the new products enable the continuation of such art at a high level.

A financial factor should, however, be added to this statement, a factor that differentiates productions at the beginning and end of the century. It is not rare to find documentation about statues that took several months if not years of finishing work (patina and engraving, in particular).

The invoice for a bronze is, therefore, only an assumption of its date.

IDENTIFYING A BRONZE

The idea of indelibly marking a bronze is not new, but is not a satisfactory solution.

How can written inscriptions that enable a bronze to be identified remain impervious to falsification?

Founders attempt to authenticate their productions and have drawn up an ethical code in which they include certain marking obligations: year of production, foundry’s signature… Certain foundries complete this information with a stamp on the bronze bearing their hallmark. Others stamp or inscribe, using a laser, a microscopic production mark, the location of which is known only to them. All these processes can be more or less easily falsified through grinding, welding and in-depth examination of the work, etc.

It is, in the end, the more simple factors that enable the identification of a moulded object: its dimensions and weight.

Founders are well aware of this reality and a large number of them have registers containing such information in relation to all objects delivered by them. Such information is not always disclosed to the sculptor or his customer. It is very difficult, without measuring, to take precise measurements of a curved hump, for example, which explains the differences found in directories, lists of artists’ works, price lists, etc.

It is, however, necessary to be very attentive to the information provided on the dimensional measurements. All metals and alloys contract in size when they solidify. The poured object has dimensions that are less than the dimensions of the model used. This remark is particularly interesting where works are ‘overlaid’ over older works. The second part will, therefore, have dimensions that are smaller than the ‘mother’ work.

What should also be emphasized are the difficulties in obtaining exact measurements of ungainly forms, the extremities of which have been altered by engraving, by accidents, by adding metal, whether voluntary or otherwise. This is particularly true for works having small dimensions.

The weight of an object is, conversely, more difficult to copy, because it arises from the thickness of the work, which is extremely difficult to monitor in a rigorous manner. Adding metallic weight to an object leaves easily identifiable traces (when the interior of the object is accessed).

THE LEGISLATION

A/ AUTHORS’ RIGHTS

The fundamental law in France governing authors’ rights dates from 11 March 1957 (1). It was completed and modernized in 1985 (software protection, adaptation to different methods of reproduction…). In 1992, this law was transposed as the basis of the new Code of Intellectual Property. The latest reform to authors’ rights, in 1997, relates to the period of protection granted to artists.

• The authors’ rights

The first Article of the Code of Intellectual Property provides a concise definition of the nature of authors’ rights:

Article L.111-1: “The author of a creative work possesses, from the sole fact of its creation, an intangible, exclusive and universally enforceable right of ownership.

This right includes attributes of an intellectual and moral nature as well as attributes of a pecuniary nature as determined in Books I and III of the Code.

The existence or entering into of a contract for hire or of service by the author of the creative work does not in any way derogate from the possession of the right referred to in the first paragraph (L. no. 57-298 of 11 March 1957, Art. 1).”

The author’s right has the particularity of being dualistic because it is comprised of both moral and pecuniary rights.

The moral rights include the right to disclose, the right to respect, the right of origin, the right to withdraw or reconsider (5). Such rights are personal, perpetual and unalienable.

The pecuniary rights include the right to exploit (6), the right to reproduce (7), the right to perform (8) and the right to royalties (9). These rights are assignable (10) and are protected during the “period of the author’s rights” from a date determined by the law. Such rights can be transmitted to heirs or legatees after the death of the artist.

• The period of the author’s right in relation to pecuniary rights

It was created:

– to reconcile the interests of the creator with those of art enthusiasts (who benefit from having works fall into the public domain). The legislator protects the artist and offers society ‘a right to intellectually use the work’,

– in order to be effective; in 1815, a French essay attempted to prove that perpetuating pecuniary rights would lead to aberrations. After three generations, more than 100 people would share in the rights, a derisory situation.

Nonetheless, since its creation in the 18th century, the pecuniary rights protection period has not ceased to increase: 10 years in 1793, 20 years in 1810, 30 years in 1854, then 50 years in 1866, 50 years + 6 years and 152 days in 1919, 50 years + 14 years and 272 days in 1951 and, lastly, 70 years in 1997.

The leading international laws that define the period of protection of literary and artistic works are:

Article 7.6 of the Berne Convention (11), which provides that the period of application of the author’s rights is a minimum of 50 years, certain countries being able to grant a longer period of protection.

In relation to other countries, Article IV.2 of the Universal Copyright Convention (12) stipulates that the protection cannot be less than 25 years after the death of the author.

The two Conventions are unanimous in defining the protection of works in foreign countries: “In any case, the term shall be governed by the legislation of the country where protection is claimed; however, unless the legislation of that country otherwise provides, the term shall not exceed the term fixed in the country of origin of the work.”

(Art. 7. 8 Berne Conv./Art. 4. 4 Universal Copyright Conv.)

In March 1997, the French legislature voted a law harmonizing French law with European law.

Among other things, it extended the period of the author’s rights accorded in 1866. Henceforth, Art. L.123-1 stipulates that: “The author shall possess, during his lifetime, the exclusive right to exploit his work in any form whatsoever and to derive monetary profit from it. On the death of the author, that right shall subsist for his successors in title for the current calendar year and 70 years thereafter”.

This Law 97-283 (Official Journal of 28 March 1997) applied retroactively from 1.07.1995 and followed Directive 93/98 (13) of 29.10.1993 that sought to harmonize all European laws on the period of application of author’s rights.

This European ‘harmonization’ did pose application problems, in particular in relation to extensions during wartime. The European Directive does not refer to this situation, unlike the French legislation, and it has still not determined if the war years are included in the new period of 70 years. Thus, the law voted in March 1997 does not repeal the relevant articles.

• Extensions for war

These were for the purpose of extending the period of protection for works in order to ‘indemnify’ authors’ successors from disturbances arising from and suffered during the two world wars; financial constraints, difficulties in advertising, weakened market…

They are governed by two provisions of the Code of Intellectual Property:

Article L.123-8 (Law of 3.02.1919, Art. 1): “The rights accorded by the Law of 14 July 1866 on the rights of heirs and successors-in-title of authors to the heirs and other successors-in-title of authors, composers or artists shall be extended for a period equal to that which elapsed between 2 August 1914 and the end of the year following the date of the signing of the peace treaty, for works published prior to that latter date and which had not fallen into the public domain as at 3 February 1919”, ie, 6 years and 152 days.

Article L.123-9 (Law 51-1119 of 21.09.1951, Art. 1): “The rights are extended by a “period equal to that which elapsed between 3 September 1939 and 1 January 1948 for all works published before that date and that had not fallen into the public domain as at 13 August 1941”, ie, 8 years and 120 days. Or 14 years and 272 days for the two cumulative periods.

To which should be added 30 additional years if the author died for France (Art. L.123-10, eighth paragraph).

• Posthumous works

Until 1997, posthumous works were governed by the regime contained in the Law of 1957, Art. L.123-4 of the Code of Intellectual Property: “for posthumous works, the period of the exclusive right is 50 years from the date of publication of the work…

The right to exploit posthumous works belongs to the author’s successors if the work was released during the period provided in Art. L.123-1.

If the release was made after the expiry of this period, it is for the owners of the work, whether by way of succession or other ownership title, to publish the work or have it published.

Posthumous works must be the subject of separate publication, except where they constitute part of a work that has been published previously. They cannot be attached to works of the same author that have been previously published. They can be attached to works of the same author that have been previously published only if the author’s successors continue to possess the right to exploit such work.”

Since 27 March 1997, the transposing law in European Directive 93-98, which significantly reduces the period of protection for posthumous works, must be taken into account. The new wording of Art. L.123-4 of the Code of Intellectual Property distinguishes between works published or unpublished during the period of monopoly under the author’s rights.

If the posthumous work is published while the period of protection of the author’s rights (70 years) on works published during the life of the author continues to apply, the monopoly attached to the publication of the posthumous work will continue until the expiry of such period. If the publication of the posthumous work begins after the expiry of this period, the exclusivity period will be “25 years from 1 January of the calendar year following that of publication”.

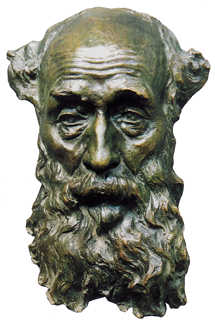

Man’s Mask style=”text-decoration: underline;”>, attributed to Rodin (not recognized by the Rodin Museum). Original cast using lost-wax technique

Rodin died in 1917. At that time, the Law of 14 July 1866 applied, providing that the exclusivity period for his successors was 50 years after his death. The exploitation of the works of Rodin having suffered as a result of the two world wars, the war years’ should be added to such period. The legatees of his works therefore benefit from the combined total of 50 years and 14 years 272 days. Consequently, Rodin works fell into the public domain in September 1982. The same applies to Camille Claudel, who died in 1943. Her heirs benefit from the Law of 27 March 1997, which extends the period of rights to 70 years. The works will fall within the public domain in April 2014, unless the French legislator decides to grant supplementary years as a result of war. In such case, a further 8 years and 120 days should be added, the protected period therefore expiring in 2022.

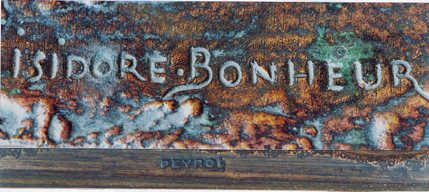

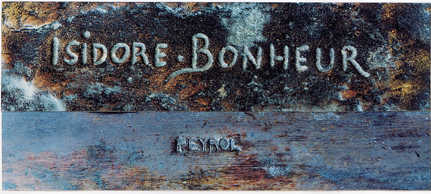

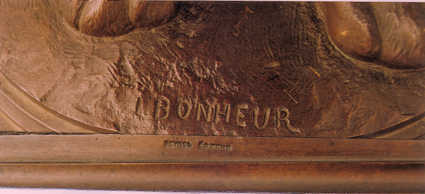

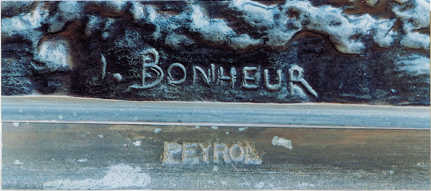

Signatures, Pierre Jules Mène and Isidore Bonheur

Artists whose works have fallen into the public domain and whose heirs’ rights have lapsed are, nonetheless, protected by the public prosecutor and by consumer associations who may join any proceedings as civil parties.

This is the finding of a judgment of 14 January 1993 (13th Chamber, Section B) delivered on an appeal from a judgment of the Paris Regional Court (31st Chamber, 9 April 1992) in the case involving Mr Guy Hain and the Public Prosecutor, as appellant, and Mr Robert Stratmore, an art enthusiast, civil party appellant and the federal consumers’ union, civil party appellant.

Not only was Mr Guy Hain found guilty of having misled his co-contracting party on the substantial nature and origin of the works by selling bronze sculptures falsely attributed, through their signature, to Pierre Jules Mene and Isidore Bonheur, but he was also found guilty of having breached “the right to respect of the name of the artist in question, the quality of their work, such right being perpetual, inalienable and imprescriptible”.

This judgment marks a major turning point in the trading of copies of artists the rights to reproduce for which have fallen into the public domain. It warns, for example, the producers and sellers of bronzes made using the overlaying technique, which deforms the work through a poor production or patina quality, by applying the inalienable rights to respect and disclosure to such works.

On the presentation a veritable flood of counterfeit works, in breach of the rights of artists P.J. Mene and I. Bonheur, whose works had fallen into the public domain: the experts, considering that the overlay moulded works discovered in this operation were inept, heavy-handed and of poor quality, that the copies examined had been produced from current bronze copies, [the Court held] “that pursuant to Art. 6 of the Law of 11 March 1957 on literary and artistic ownership, the author (who Art. 8 of that Law defines as being the person in whose name the work is disclosed)

had the right to respect of his name, status and his work and that this right was perpetual, inalienable and imprescriptible; that the fact that the accused had offered poorly produced recent copies for sale and falsely attributed them to well-known animal sculptors of 19th century unquestionably constituted a breach of the right of origin and respect in the works of Pierre Jules Mene and Isidore Bonheur

and therefore constituted the offense of counterfeiting through release of a creative work in breach of the authors’ rights provided in Art. 426 of the (French) Criminal Code; the judgment under appeal should, therefore, be set aside and Guy Hain be declared to be guilty of counterfeiting through the release of creative works in breach of the moral rights of the authors Isidore Bonheur and Pierre Jules Mene”.

1 Provided in Art. L.121-1 of the Code of Intellectual Property.

2 Provided in Art. L.113-1 of the Code of Intellectual Property.

3 Judgment no. 2 of the Paris Court of Appeal, 13th Chamber, pp. 12-13.

B/ OFFICIAL PROVISIONS

In compliance with the Law of 8 March 1935 (O.J., 10 March 1935), ‘bronze works of art’ must be produced from a metal alloy (14) in which the proportion of copper cannot be less than 65% of the total weight of the object being produced.

The producing of a bronze from an original model poses a problem that is inherent in the casting of the material. A bronze is not an original work within the same meaning that we apply to a painting, for example. It is, from the start, a reproduction. In addition, a bronze is really a unique object, the choice of material and method of production involving multiplicity.

In order for a work to be recognized and protected by the law, it needs to have an original character (15), ie, it reflects the personality of its author. However, a bronze is necessarily the technical reproduction of a pre-existing original model (in plaster or other malleable material) created by the artist.

The legislator takes this singularity into account and provides limits in order to govern bronze productions. It confers the status of a stand-alone work of art, taking account of its ‘non-uniqueness’.

The legislator provides two clauses under which the original nature of the bronze work can be attributed:

– For practical and tax requirements, the ‘original’ bronze must be a limited edition. The public authorities have produced a Decree that determines the number of authorized and ‘original’ copies to be eight.

– The bronzes are required to be produced “from a model having identical proportions and dimensions to that produced by the artist”. Up to eight posthumous castings having such qualities can be considered to be original works. The works, which are not strictly and in all ways identical to that of the artist, must be considered to be reproductions.

These limitations on original copies, as arbitrary as they seem, enable the protection of ‘original’ works of art against excessive castings that devalue bronzes.

In addition to the eight ‘originals’, the authorities allow four ‘artist’s copies’ that feature a distinctive mark (I/IV to IV/IV from 1 January 1968). These works are reserved for the artist and his successors and French and foreign cultural institutions and cannot be commercialized. However, they benefit from the same tax regime as the first eight copies. The Decree of 10.06.1967 entered into force on 1 January 1968.

It should be noted, however, that these four copies are often commercialized by the artist, galleries or auction houses. In the eyes of art enthusiasts and the tax authorities, these four supplementary copies have the same value as the first eight copies.

Article 71-3 of Appendix III to the (French) General Tax Code:

Original works of art are considered to be “productions in any statue, sculptural or assembling art material, where such productions and assembled works are produced entirely by the artist (…) Casts of sculptures limited to eight copies and supervised by the artist or his successors”.

Which means that these eight “originals” in bronze must be numbered (from 1/8 to 8/8 from 1 January 1968).

Also considered to be original works of art are casts of sculptures produced from a mould that is identical to the initial work, subject to their copies, limited to eight and four, being supervised by the artist or his successors.

This description does not concern the moulds for the casting of sculptures.

In 1995, Decree 95-172 redefined these copies as “works of art” and repealed Art. 71-3.

Extracts from the case law:

“An original copy of a graphical or fine art work is an object that can be considered as having arisen from the artist’s hand or that was produced according to his instructions and under his control such that, even in its production, this material support bears the mark of the personality of its creator and can be distinguished from a mere reproduction”. Civ. 1st, 13 Oct. 1993; see Note 1.

“The concept of original is distinct from that of uniqueness, such that several copies of the same creation may exist…” Civ. 1st, 15 Nov. 1991: see Note 2.

“Limited edition bronze copies cast from a model that entirely is the source of their originality should also be considered to be works resulting from the hands of the artist, (…) the fact that the limited edition bronze copies are produced after the death of the sculptor has no influence on the original nature of the work and the personal creation”, Civ. 1st, 18 March 1986: see Note 2.

Since 3 March 1981, Decree 81-255 on the prevention of fraud in transactions relating to works of art and collector items:

Article 9: “Any facsimile, over-laid mould, copy or other reproduction of an original work of art within the meaning of Art. 71 of Appendix III of the General Tax Code that is produced after the date of entry into force of this Decree must bear, in a visible and indelible manner, the mark ‘reproduction’.”

The Law of 9.04.1910 stipulates that the reproduction right is no longer attached to the work, as before, but is the ‘privilege’ of its author.

The sale of work of art does not lead to the assignment of the author’s rights to the new owner unless the author provides otherwise.

Column in the Place Vendôme

Napoléon To commemorate the glory of his soldiers winning the battle of Austerlitz, Napoleon had a column erected in the centre of the Place Vendome on the pedestal of the former statue of Louis XIV. Forty-four metres high, it was cast by Lepère and Gondouin from 1806 to 1810 from 1,250 cannons taken from the Russians and Austrians. A spiral of 76 bronze reliefs circling a stone shaft represents the soldiers and armies in the campaign of 1805.

In 1810, it was topped by a statue by Chaudet representing Napoleon as a Roman emperor. This was replaced by a white flag in 1814 then, in 1818, by an enormous fleur-de-lys.

In 1833, a new statue of Napoleon in a frock coat and hat was installed and the base of the column refurbished in Corsican granite. In the 1860s, Napoleon III substituted the statute with what is currently seen today, produced by Dumont, where the emperor is again seen in Roman clothes.

In May 1871, during the Commune civil war, the column was removed and mutilated under the direction of the painter Courbet, then, in 1873, was again installed, at the latter’s cost.

The right to reproduce this column fell into the public domain after the expiry of the period of protection. Anyone can, therefore, produce copies, reduced-size copies or photographs. This is not the case for all works found in a public place, the reproduction rights to which may still belong to the artist or his successors.

The works of César or Buren, for example, cannot be photographed for commercial purposes without their authorization and their associated rights must be complied with.

Jeanne d’Arc, E. Frémiet, 1874-1889.

Place des pyramides, Paris.

Despite numerous smaller-scale reproductions, this large statue is a unique work. Frémiet increased the dimensions of Jeanne d’Arc compared to the initial model that had served as model for the reduced-size series.

THE VALUE OF WORK OF ART

The principal factors in valuing a work of art are:

– the quality of its production, engraving, patina, etc,

– its aesthetics, the emotion and imagination it provokes,

– its place in the history of art and the artist,

– its rarity, the number copies made,

– its authenticity,

– its age,

– for bronzes, the name and reputation of the founder,

– its speculative interest, its official price in the international art market,

– its filiation,

– the quality of the seller.

The combination of these various factors gives rise to the value of a work of art at a given time. It is clear that this price involves fluctuating factors that may vary substantially.

The expert, through his visual analysis of the work, his knowledge of the artist, his experience in its production techniques, his documentation on the art market and art prices, gives an estimation of the item in question and his approval to the physical and general descriptions proposed by the seller.

In the end, the value of a work of art is the price that a buyer decides to pay in order to have it in his possession. Such price may substantially vary depending on the number of art enthusiasts present at an auction.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the actual sale price of a work may be considerably different from the estimation by the expert, who may not take into account current fluctuations in such valuation.

Other information may, however, assist in informing the expert art professional:

– the moulding technique used, traces of the materials used (found inside the object) such as sand, moulding layers and coatings,

– types and qualities of assembling objects used in different parts of the work (screws, pins, threaded rods, etc),

– physical traces of engraving, nature of the patinas, etc,

– previous, related, expert art reports,

– customary practice by founders, engravers and patineurs leaving visible traces,

– for sand cast bronzes, details of the joints of the models, the number of which enables determination of the number of moulded pieces.

The existence of antique items that have been restored through the reconstitution of deteriorated parts, by welding or pieces cast or welded to the original, should also be mentioned.

All of these observations are associated and can provide the expert with a multitude of assumptions, the concordance of which enables him to provide his opinion on the object being examined.

Only an art professional, perfectly aware of foundry and sculpture techniques, can provide a reliable opinion.

|

|

Theseus striking down the centaur Bienor, Antoine Louis Barye. Very rare bronze in its original size, 1 m high, cast by Barbedienne, signed Barye and dated 1860. A series of four smaller-scale statues were produced before and after the artist’s death in 1875. All of the works cast in the 19th century are today considered to be originals, which leads to a certain amount of confusion for the uninitiated. |

|

NOTES

1/ Law 57-298 on literary and artistic ownership, Civil Code. It is comprised of 81 Articles that constitute nearly all of the first Book of the Code of Intellectual Property.

2/ Article L.121-2: “Only the author has the right to disclose his work. Subject to the provisions in Art. L.1321-24, he determines the process for disclosure and its conditions. After his death, the right to posthumously disclose his work is exercised, during their lifetime, by the legatees nominated by the author. In the absence or after their death and unless otherwise specified by the author, such right is exercised in the following order: by the descendants, by the spouse against whom no final separation of property judgment has been delivered or marriage contract entered into, by the heirs other than the descendants who receive all part of the estate and by the universal legatees or donees of the future universal property. This right may be exercised even after the expiry of the exclusive exploitation right referred to in Art. L.123-1.”

3/ Article L.121-1: “The author has the right to respect for his name, authorship and work. This right is attached to him personally. It is perpetual, inalienable and imprescriptible. It may be transmitted on death to the author’s heirs. The exercising of the right may be conferred on a third party pursuant to a will.”

4/ Article L.113-1: “Unless otherwise proven, authorship belongs to the person or persons under whose name the work has been disclosed.”

5/ Article L.121-4: “Notwithstanding the assignment of his right of exploitation, the author possesses a right to reconsider or withdraw, even after publication of his work, with respect to the assignee. However, he may only exercise that right on the condition that he first indemnify the assignee for any prejudice the reconsideration or withdrawal may cause him. If the author decides to have his work published after having exercised his right to reconsider or withdraw, he is required to offer his rights of exploitation first to the assignee he originally chose and under the conditions initially determined.”

6/ Article L.122-1: “The right of exploitation belonging to the author comprises the right to perform and the right to reproduce.”

7/ Article L.122-3: “Reproduction consists of the physical fixation of a work by any process permitting it to be communicated to the public in an indirect way. It may be carried out, in particular, by printing, drawing, engraving, photography, moulding and all graphical and fine arts, mechanical, cinematographic or magnetic recording processes. In the case of architectural works, reproduction also consists of the repeated production of a plan or of a standard project.”

8/ Article L.122-2: “Performance consists of the communication of the work to the public by any process whatsoever by way of:

1. public recitation, lyrical performance, dramatic performance, public presentation, public projection and transmission in a public place of a broadcast work;

2. Broadcasting. Broadcasting means the distribution of sounds, images, documents, data and messages of any kind by any telecommunication process. Transmission of a work to a satellite is the same as a performance.”

<

p style=”text-align: justify;”>9/ This right enables the artist’s associate to benefit from any capital gain from his work. Article L.122-8: Authors of graphic and three-dimensional works, regardless of any transfer of the original work, have an inalienable right to participate in the proceeds of any sale of such work by public auction or through a dealer. The royalty levied is a uniform 3% applicable only to a selling price that is above an amount to be laid down by regulation. This royalty is levied on the selling price of each work and on the full price with no deduction from such base.

10/ Article L.122-7: “The right to perform and the right to reproduce may be transferred, with or without payment.

Transfer of the right to perform does not imply transfer of the right to reproduce.

Transfer of the right to reproduce does not imply transfer of the right to perform.

Where a contract contains the full transfer of either of the rights referred to in this Article, its effect is limited to the terms on exploitation specified in the contract.

11/ Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works signed in Berne on 9 Sept. 1886, revised and completed in the 20th century, published in Decree 74-743 of 21 August 1974 (O.J. of 28 August).

12/ Universal Copyright Convention signed in Geneva on 6 September 1952 and revised in France on 24 July 1971. Published in Decree 74-842 of 4 October 1974 (O.J. of 10 Oct.) – Entry into force 10 July 1974

13/ EC Directive 93/98 of 29 October 1993: Art. 1 – Duration of authors’ rights. “1. The rights of an author of a literary or artistic work within the meaning of Article 2 of the Berne Convention shall run for the life of the author and for 70 years after his death, irrespective of the date when the work is lawfully made available to the public.”

14/ Bronze is an alloy of copper, tin and zinc.

15/ The author’s rights require two conditions to be met in order to protect a work of art: the necessity for a creative form and the necessity for originality. The work must be produced on a material medium, which distinguishes it from the concept of lawful exploitation by more than one person. The originality corresponds to the artist’s creativity.