The force of a belief beyond reasonable doubt in an expert report

The author recounts the examination of an unknown and unsigned statuette that took 25 years to complete. His initial “belief beyond reasonable doubt” led him to discover and index an accumulation of clues that confirmed that the statuette could clearly be attributed to Auguste Rodin, circa 1886

Article Revue Experts n°98, October 2011, pages 17 to 19.

A belief beyond reasonable doubt when examining works of art is the result of experience and does not, in itself, constitute proof. To acquire such indisputable authority, it must be based on facts, whether they be historical, stylistic, technical or scientific. Can a belief beyond reasonable doubt assist the expert and to what extent? From my own experience, it increases hope and perseverance. The dictionary defines such belief as being “the result of a manifest proof in the mind, certitude in the truth of a fact, a principle” or “the fact of being convinced of something, a feeling by someone who firmly believes in what he thinks, says or does”. The expert examination that I present in this article lasted nearly 25 years and without holding a belief beyond reasonable doubt, I would not have had the perseverance to find such proof and publish the result.

1. THE DISCOVERY

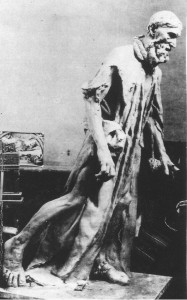

In 1987, Christian C., an antiques dealer in Nantes, discovered, when bargain-hunting, a black patina, white metal, statuette that a flea-market dealer in Saint Ouen sold to him, considering it to be of babbit metal[1]. Once back at his boutique, he cleaned it and discovered that it was made of unstamped silver that did not contain any trace of a signature or the founder (photo 1). He carried out some visual comparison research, which led him to the end of the 19th century and, more specifically, to Auguste Rodin. Based on his considerable experience in Renaissance bronzes, his various stylistic deductions were sufficient for him to forge an opinion: this work must be that of the master sculptor. Nonetheless, not being an undisputed specialist in works of the presumed artist, he was careful enough to sell his ‘treasure‘ as being attributed to Rodin, with no guarantee other than his belief beyond reasonable doubt. Such intuition would be transferred to the new owner.

Photo n°1

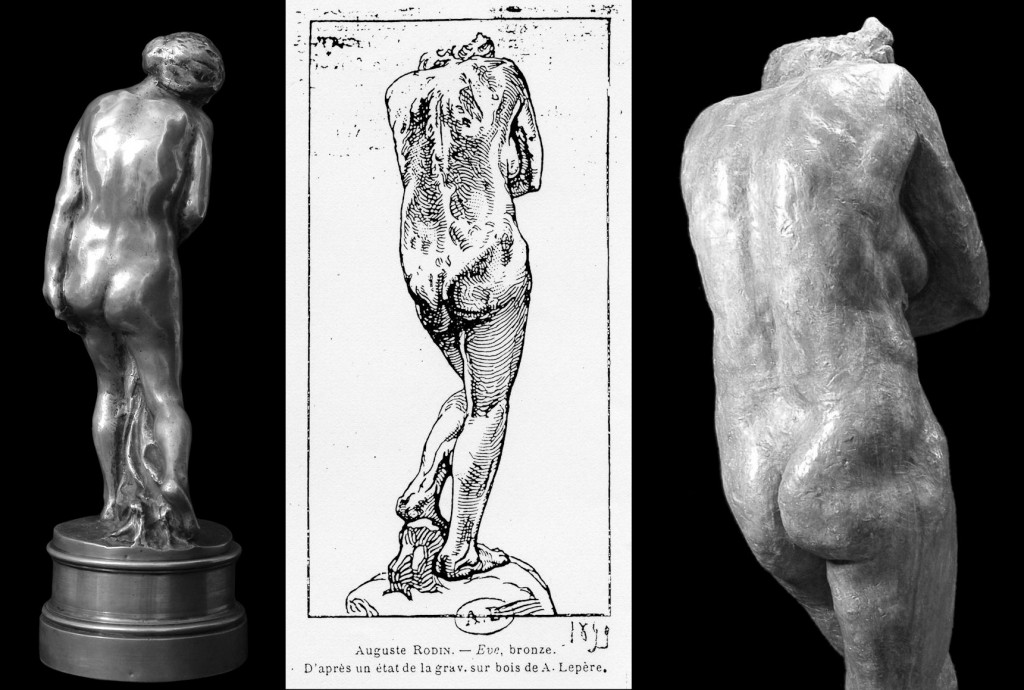

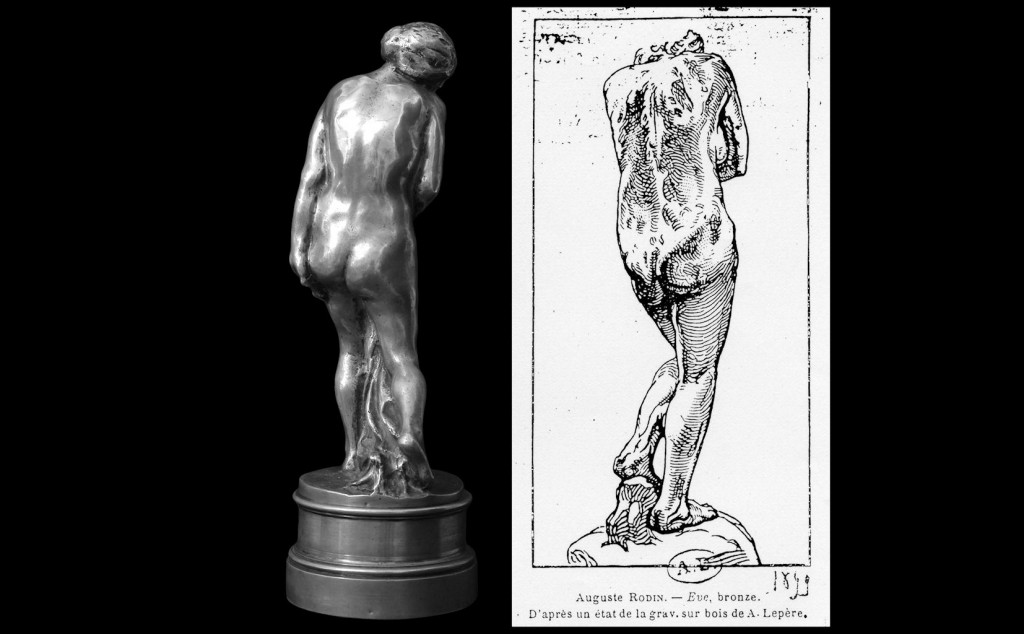

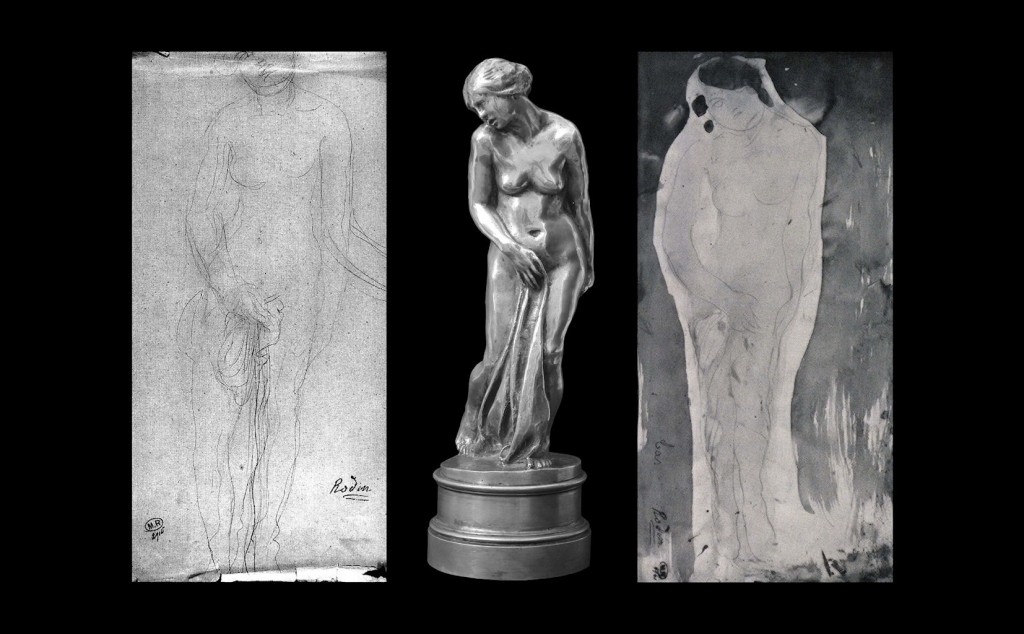

From the beginning, I was certain that the work was that of Auguste Rodin or Camille Claudel from the time they were in love. I was unable to put it down as, from the start of my research, I discovered that this statuette was the same as that which had given form to Auguste Rodin’s Eve (1881) and a rough drawing by Camille Claudel published in the 1886 edition of L’Art: one of the famous “Abruzzesi” (photo 23). Being all of thirty-five at the time, I naively immediately attributed the work to a common fruit of the love of the two sculptors.

Mrs P, a great-niece of Camille Claudel, initially thought my conclusion brilliant. At her request, I did not hesitate to organise a travelling exhibition in Asia of the works of Camille Claudel to follow those organised by the Rodin Museum for the works of her mentor. The first exhibition opened in 1993 at the French Consulate-General in Hong Kong for the ‘French May’. Rodin was several hundred metres away on the other side of the river, at the fine arts museum.

My relationship with Mrs P quickly deteriorated when preparing the transportation in Paris, as I discovered that this ardent defender of Camille had lent mainly posthumous works to the exhibition, some of which I contested the origin, like a recent reproduction in gold of the The Waltz or a copy of Wave in bronze.

I therefore quickly had a brochure printed in English describing each work in detail, noting whether they had been produced whilst the artist was still alive or posthumously. This had an immediate effect, with the local press acclaiming, above all, the beauty of the silver statuette. Mrs P, offended, requested that her partial contribution to the Camille Claudel exhibition be removed. As a fervent defender of her great aunt, she even subsequently complained that I had included this statuette in her catalogue against her wishes (author’s rights).

My act of high treason relegated the statuette back to square one. A presentation of the statuette to the head curator at the Rodin museum, Nicole Barbier, in February 1993 as a work in common between Camille Claudel and Auguste Rodin was abandoned. I would have to restart from zero.

And the owner? He who had sought me out for this research? By renewing his total confidence in the grounds for my opinion, he no doubt signed a pact of friendship that enabled me to continue my research for another eighteen years. He had a belief beyond reasonable doubt that I would, in the end, find other proof.

2. THE GERMAN TRAIL

In 1995, a new trail opened when I learnt that Auguste Rodin had exhibited ‘statuettes’ in 1885 at the precious metallic objects exposition in Nuremburg. He shared the editor Rouam’s stand with the sculptor Ringel. The silver statuette was not originally stamped – artist’s works exhibited at international expositions were exempt from tax, therefore exempt from the guarantee stamp. I therefore directed my research towards Nuremburg … alas, none of the contacts I made provided a response to the subject of the Rouam stand. It was only ten years later that I discovered that Rodin had only sent two bronze copies of Ixelles Idyll (of different sizes) to this exposition. Maybe he had intended to send a silver statuette to the exposition? No written document corroborates this hypothesis. This trail only leading to a dead-end, I returned to my point of departure and sought assistance from an art historian with considerable experience in 19th-century sculptures and researching archives and libraries, Anne Riviere[2].

3. THE SEARCH OF PROOF

In 1999, she sent me her report: her opinion corroborated mine without, alas, providing any new proof[3]. At the time, I was fully occupied with an expert criminal report of more than two thousand five hundred models and bronzes from the 19th century, including Rodin and Camille Claudel[4]. Somewhat disappointed, I abandoned my research for several years until I received a new court expert mission in relation to 51 Rodin works[5]. The starting point for a criminal report is always clear, but never the direction in which it might take you. This report took my colleagues and I to Canada, Italy then to various exposition sites (museums) and manufacturing sites (foundries) in France. Each item was examined on site then compared with original or counterfeit works and molds and master models held by the Rodin museum.

These two cases and other less significant cases, totalling 10 years’ investigation into Rodin’s works[6], enabled me to discover new evidence.

The silver sculpture constantly reappears in a section of his works. It was present, invisible but omnipresent, both in the contrapposto of The Shade and Adam, in the positioning of the hands in The Kiss and Eternel Spring and in the muscles in Eve, in particular. All works created by the master sculptor after Age of Bronze until 1890 contained a part of the unknown lady. When, by chance, the original plaster of a work under investigation still existed in the Rodin museum’s storage, each time it increased the importance of this connection. I therefore recommenced my search, benefiting from such access to classify some revealing photos.

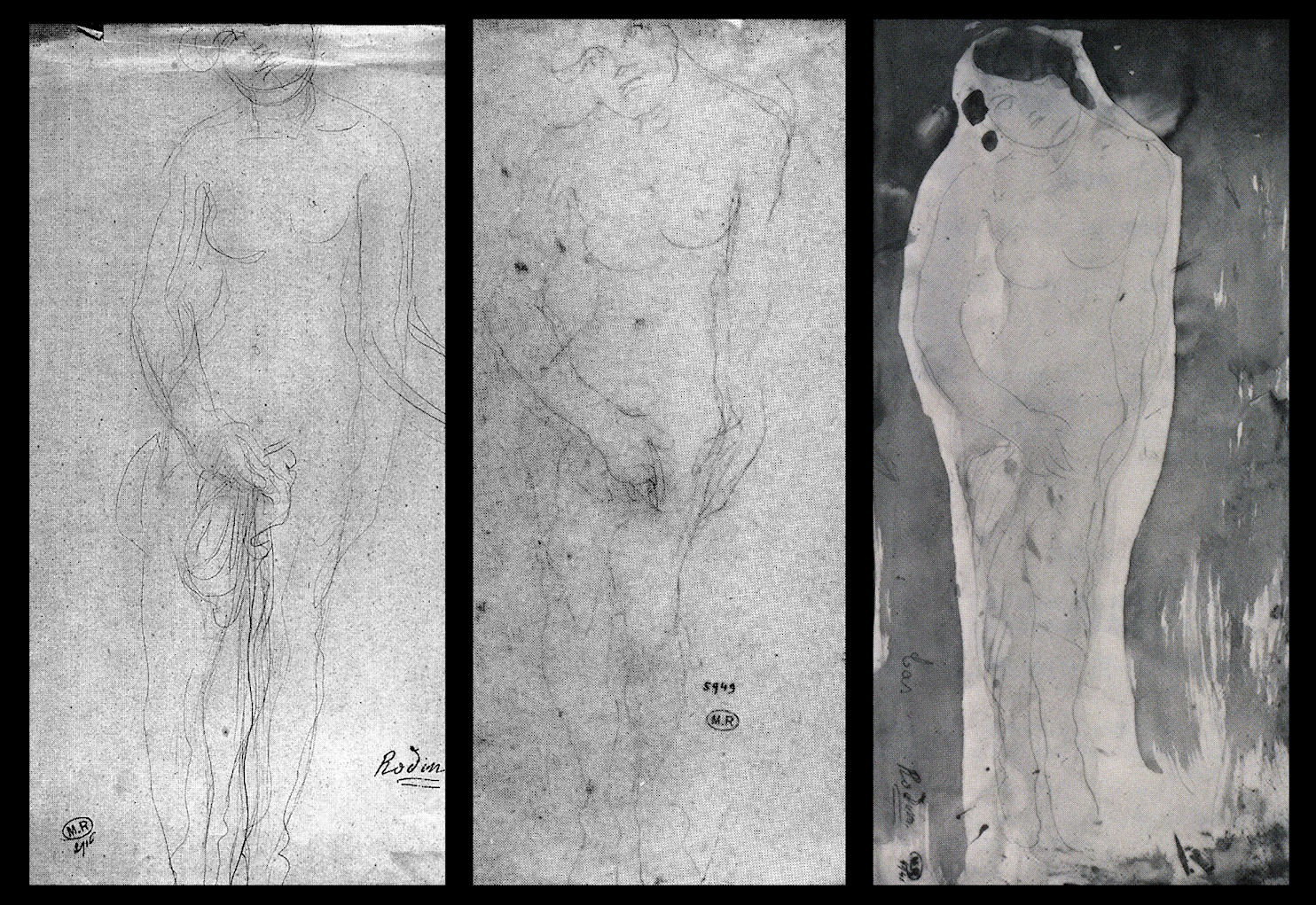

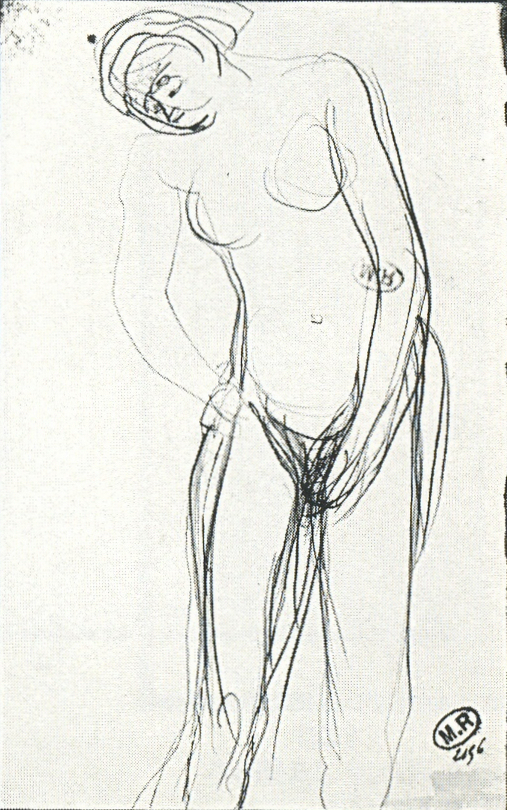

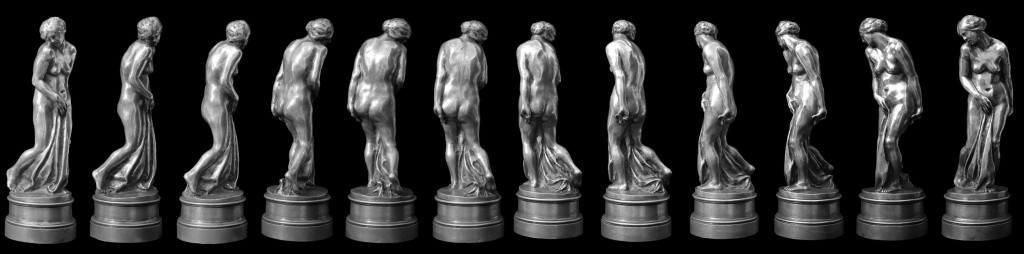

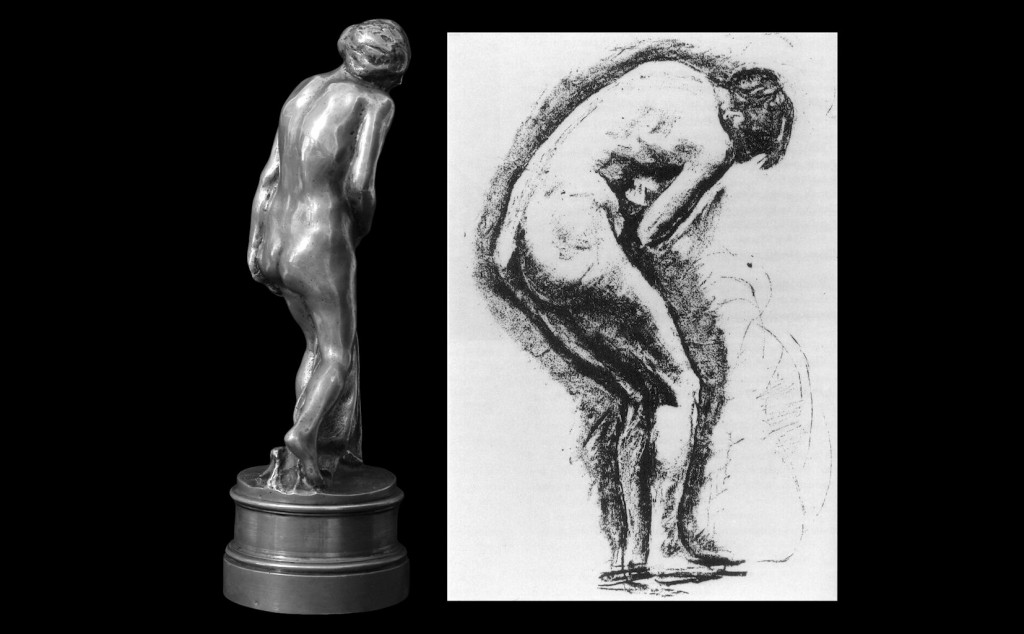

In summer 2007, my belief was so firmly held that I decided to re-examine all of the illustrations research and re-read all of the texts written about Rodin’s work. This new departure bore its fruit. I discovered sketches by the master sculptor dated 1885, some of them reproducing exactly the same posture (photos 2, 3 & 4) and, for others, elements of the work in question. They reinforced my view. I had, for more than twenty years and, as a precautionary measure, evidently examined all sketches and sculptures that were significantly or even insignificantly similar to the silver statuette. I also examined the work of Rodin’s contemporaries: Jules Dalou, Antoine Bourdelle, Emile Bernard, Jules Desbois, Paul Dubois … and many other artists. I criss-crossed France from north to south and east to west, never hesitating to return, even numerous times, to museums in Roubaix (La Piscine), Rouen (fine arts museum), Morlaix and Jules Desbois in Nogent sur Marne, without omitting, obviously, the Paris museums (including Orsay).

- photos n°2 à 4

- Photo n°5

It is clear that while Auguste Rodin never drew preparatory designs of his works, he did, however, do sketches to illustrate an idea or a posture. Following his trip to Italy in 1875, the discovery of the Michelangelo contrapposto in Florence was a revelation that affected all of his later works. The sketches in his workbooks show that the posture of the statuette in silver interested him enough to reproduce it on several occasions. The lesson from the Michelangelo work: the form is a reflection of interior feeling and truth. Academic art studied at the Louvre no more. The body should be a mirror of the soul. Rodin incessantly expressed “the painful redeployment of a soul within a body, the troubling energy, the desire to act without hope of success”, etc.

- photos n°6 à 8

- photos n°9 à 11

4. STYLISTIC COMPARISONS

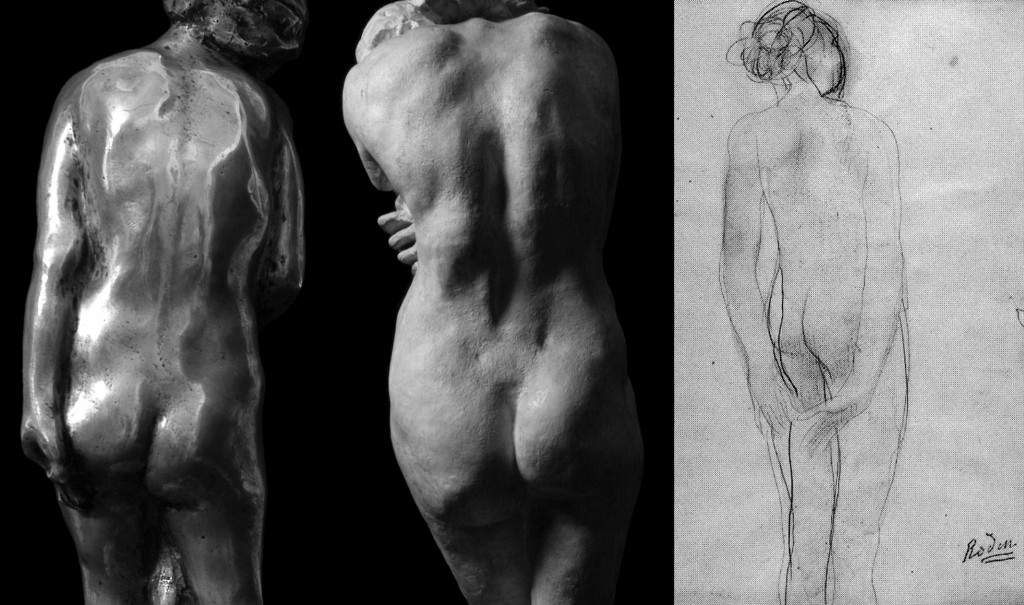

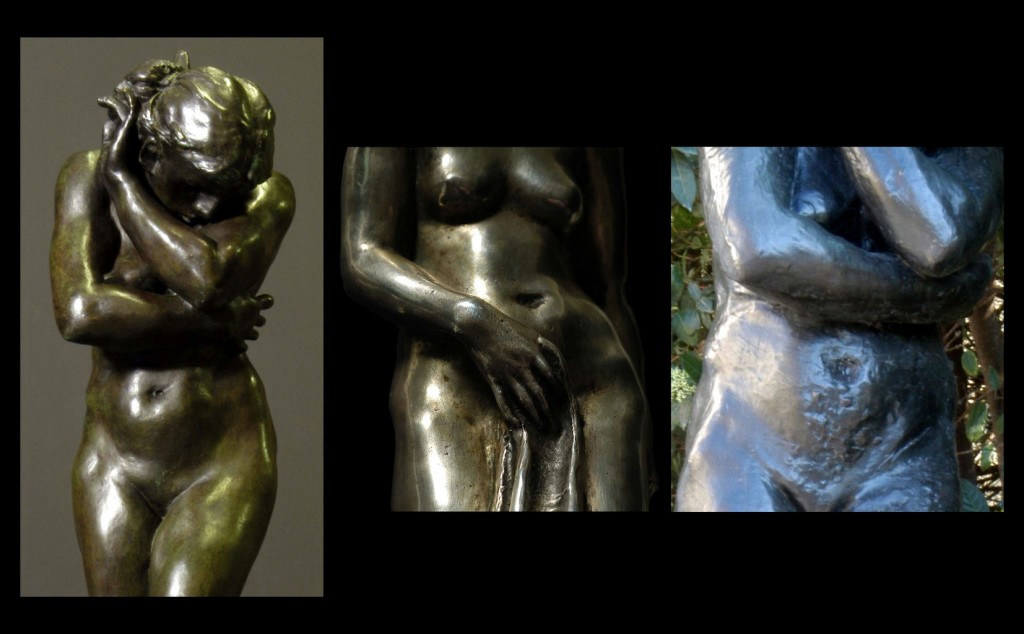

One of the statuette’s aspects is that of interiorization, which is often found in Rodin’s work on his return from Italy until the 189os. The back is bowed, curved out in an abnormal and excessive manner. The anatomy contains a supple and rounded musculature, authentic without being exaggerated.

Its pose is very close to that of one of The Burghers of Calais. Like The Burghers, the body in question is leaning forward, weight on the left leg, with the right leg well behind and slightly bent, the arms hanging down alongside the body. Like Eustache de Saint-Pierre’s tunic, the sheet held by the woman falls vertically between her legs with long, flat, close, creases, folding back on itself at the base. The cloth merges between the legs and the base. This pyramid shape is found in the Naked Balzac, I Am Beautiful and Little Fauness where a conical form extends from the ground up to the figure.

- photos n°14 à 16

In continuing my observations of this silver sculpture beyond an overall view, my stylistic research revealed a number of analogies between works of the master sculptor. I have presented these in themes in order to clarify this demonstration. The photographs are sorted by movement, limbs or parts of the body in sketches then sculptures. However, the overall positioning being frequent in Rodin’s work, some works illustrate both the overall posture and the distortion of the neck or the position of the legs.

- photos n°17 et 18

The pose is a synthesis of Michelangelo’s Slaves[7], the Venus antiques Medicis and Capitol, which, at that time, captivated Rodin: “I have a small masterpiece that has for some time now perturbed what I customarily see, my mind and all of my experience. I owe it a profound debt of gratitude because it makes me think. This figure is from the same era as Venus de Milo … one of the arms, held to one side and behind, is overshadowed by a light tonal contrast. The movement of the other arms extends the cloth to the thighs, amassing an ardent shadow below the stomach.”[8] This description also applies to our silver sculpture.

He understood how Michelangelo obtained dramatic effects by structuring the human body and by pushing the limits of his possibilities, not hesitating to martyrize his models to obtain a particular pose. The contrapposto that Rodin began to explore in 1878 is reflected in his works: The Burghers of Calais, the national defense group of works, The Gates of Hell. In the work in question, the contrapposto inflicted fewer restrictions on the model, but remains very present (photos 1, 2, 3 and 4). The interplay between the extended arm and the other, folded, arm, one leg supporting the weight of the body and the other, bent and pivoting backwards, reflects a considerable degree of aesthetic boldness (photos 25, 26, 28 and 29). This pose is far from being banal, it is intelligently arranged to express a dramatic message that is far from the pleasant fantasies of the artists of that era.

- photos n°19 à 21

The hair commences with an initial parting in the centre and several swift applications of sculpting tools. Simplified in a bun, it forms a type of cap (photos 6 and 10). The two artists often used this manner of presenting a woman’s hair. It can be found in Rodin’s The Kiss and The Little Water Fairy and in Camille’s Sakountala and The Implorer.

The mouth is typical of Rodin’s work, in the form of an open wound, a small, gaping, orifice with barely formed lips associated with a suggestion of eyes (photos 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11).

The tension in the neck, due to the very inclined position of the head, is not at all natural. This movement was particularly frequently used by the master sculptor and his pupil to express abandonment, suffering and despair. It is found in a number of known works (photo 26).

The back is excessively, even abnormally, bent, almost humpbacked (photo 22). This is not surprising, given that an Italian woman from the Abruzzi region, who, at the time, modelled for Rodin and his pupils, had this typical rounded back condition (photos 23 and 24).

- photos n°22 à 24

The breasts are presented in a realistic manner. Their shape is exaggerated by the retracted position of the chest: Rodin’s Young Mother, Camille’s The Implorer.

The stomach represents femininity. Juvenile or mature, it is frequently bulging, round or has the appearance of being flabby. Rodin’s Eve has the same general anatomy and the same triangular, deep, navel.

The large hips and flat posterior form part of a vertical rectangle and are also identical to those of the large Eve (photos 19 and 20)

The hands are essential items in identifying the artist’s signature, such are their forms and positioning characteristic of Rodin’s models until 1890. The palm is large below the fingers, which are long, round then tapered. The little finger in each hand is laterally rounded and clearly apart from the other fingers, again in a position that is not natural (photos 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16). The left hand is very representative of a style and a method of expression used by Rodin. In a sign that refuses self-protection, the hand is facing outwards, the palm open. The little finger and the thumb, bent, confer a very particular aspect to the hand[9](photos 17, 18 and 21).

The feet are flat and large, with a significant instep and strong heel, are as nearly all of the feet in the works of Camille and Rodin.

- Photo n°25

The cloth between the legs of the statuette forms a compact pyramid between the subject’s legs (photos 1, 19, 25 and 28). This idea was repeated a number of times by Rodin in larger, less elaborate, statues in the form of a rock, the surfaces of which were striated by a serrated chisel[10] (cf, The Bather, Naked Balzac, etc). An examination through a dissecting microscope shows that this cloth was not sculpted directly into the modelling wax. It was produced with the help of a frame of very fine tissue (silk thread), soaked in hot wax and placed between the statuette’s legs and the hand holding it. This detail is extremely important because, to my knowledge, Rodin used this technique between 1880 and 1900. No other artist had the audacity to produce ‘dressed’ works at that time with the aid of added, non-sculpted, natural materials. There are many examples in the works of this frenetic inventor who sought to create effects using different materials and contrasts. Anyone else but Rodin has been revealed as a forger. The Age of Bronze affair certainly upset him, but also strengthened his beliefs.

- Photo n°27

The deliberate use of this cloth imbibed in wax, which is in perfectly harmony with the composition of the sculpture, cannot, therefore, be the work of sculptors who conformed with the conventions of the time, such as Jules Desbois, Jules Dalou or even, in a later period, Joseph Bernard and others.

The traces of tools on the base of the work, while small, are similar to those visible on the Naked Balzac or Portrait of young woman produced prior to 1887.

- photos n°28 et 29

The cylindrical molding base is an extension of the classicism of the bases and pedestals from the Brussels period. It corresponds to the European fashion of the 1870s to 1900s and the small, Italian, Renaissance, bronzes that appealed so much to Rodin. Produced by workers in marble, wood or metal, these separate creative bases were often chosen by the artist and adapted to each work by the producer. The areas retouched to fill holes occurring during the casting are identical in the two items, as are the internal traces of the casting. The conclusion is clear: the same founder cast the two parts of the statuette.

5. THE KEY TO THE ENIGMA

For twenty years, my research included all books on Rodin and Camille. In 2007, on reading a new book[11], the famous letter that Rodin sent to Camille, called ‘the contract’[12] by historians, revealed its hidden meaning, the key to the enigma, to me. Why hadn’t I thought of it before? And why had no other historian or custodian thought the same thing over the past one hundred and ten years? In his letter, Rodin promises everything to the young Camille, twenty-four years his junior: marriage, a voyage to Italy for at least six months, a statuette as a present, living together, etc. He had previously written to her, in a passionate outburst: “I do not regret anything. Neither the ending, which seems gloomy, my life will fall into an abyss.”[13]

What reason encouraged Rodin to write such ‘contract’, in which he did not make a single promise? What did he want to obtain from Camille in return? What was at stake? His return to favour after three long months absence in England from his beloved? He certainly promises to be faithful to her. But the truth imposed by the facts is tragic! Because we know, through his friend Jessie Lipscomb[14]that Camille had four abortions or hidden pregnancies with her mentor. Late in life, Rodin dared remaining silent on these unfortunate pregnancies, which made Camille increasingly bitter towards he who had promised her everything. When his biographer Judith Cladel asked him about this subject, he replied “In such case, the duty was too evident” without further precision.

Historians agree that the first pregnancy occurred in 1887 when Camille isolated herself in the Islette Chateau, near Azay-le-Rideau. But these painful passages were so well hidden by the lovers that nothing appeared in the written documents of that time that have we have obtained. Was the October 1886 contract not in direct relationship with a pregnancy previously aborted in England? Camille lived in England from May to July. What no historian, until today, has considered is that Rodin also went to London for several days in June, being with Camille at the Lipscombs, 150 kms from the capital, where he stayed two days. To travel at that time was an adventure that needed preparation in advance and required a certain amount of money: it is difficult to see that this was simply a holiday for Camille. Such a trip cost money that she would not have been able to pay. It is more probable that Rodin was the instigator and the treasurer. At the time, Camille was focussed on two things: sculpture and Rodin. In such context, is it that dubious to consider that an emotional event took place in England well away from scandal mongering? Only the two English friends who welcomed her during these three months were her confidents. In order to keep their secret, Camille reminded them, in a letter in 1887, to burn her letters. To me, the silver statuette is an atoning, autobiographical, work. It reflects a very important secret between the two lovers.

In 1993, we called this work ‘la pudeur’ [decency]. In light of my findings and in a careful observing of its expression and features, the theme appears more tragic: this woman is suffering. Her hand covers her genitals, from which is suspended a cloth that seems to indicate the source of her pain, the other is behind her back, useless and powerless. Camille refers in her writings to a work from such time that was lost, called Le pêché [sin], then in others as La faute et la confidence [fault and confidence][15].

In such context, hardly honourable for Rodin, the silver statuette, born anonymously, became a forgotten work. Deliberately orphan, it is not signed or stamped by the founder. The artist and the recipient did not wish for any distinctive sign. However, all works at the time that were as finished as this, produced in a precious metal moreover, are at least signed by their author. Had it been simply offered to someone? Its anonymity of nearly 120 years has effaced its origin.

6. PRESENTATION OF THE WORK TO THE RODIN MUSEUM

In 1999, I wrote an initial report and presented it to the new head curator of the Rodin Museum. In reply, she noted, first, that a curator at a national museum could not carry out an expert investigation of a private work, but found the study interesting. Then she ended our interview by stating her regret at the lack of historical proof in my report: meaning known or discovered documents relating to this work. The invoice by a foundry in Bingen (addressed to Rodin) appeared to her to be too vague to be able to infer that it related to the silver statuette.

It is clearly correct that a curator of a French museum is primarily an art historian, not a technician. By protecting herself against any future commitment, was she not reminding me of my impertinence several years back? When sitting next to me on the edge of the podium of the large exhibition hall for plasters in Meudon (‘Villa des Brillants’, where Rodin had his studio), she watched me examine, for the purposes of an expert criminal report, the workshop plasters on display. I endeavoured to include in my notes the description of copies made in bronze, trying to find micro-traces in the plaster (created in the works from the sand-casting mold). When she asked me the question: “how do you know how many bronze copies have been made from each plaster?” I replied: “you are a curator, I am an expert!”. She moved away, somewhat annoyed, and we remained, for the rest of the time, in a profound silence – difficult to be more respectful of the adversarial process, even in criminal affairs.

In 2007, a new head curator and a new team were appointed, which gave me reason to again present my findings on 6 November 2008. The new counterpart from the sculptures department at the Orsay Museum was also invited to attend. I expected new trails or supplementary evidence to emerge from this meeting, but nothing new arose.

7. EPILOGUE

Fortunately, for historical purposes and with the passage of time, information eventually becomes known. Through image comparisons, letters collected by the Rodin Museum, documents published on the ‘undisclosable losses’, they begin to match and become more precise.

So much evidence and proof has been obtained from this work: it cannot, under any circumstances, be merely chance. All points to Rodin and Camille, circa 1886, excluding any doubt, removing any ambiguity.

From my experience and from twenty-four years of pugnacious research, my opinion as sculptor and expert is that this work was created by August Rodin in 1886. The autobiographical subject expressed is that of Camille’s rejection of maternity. This will undoubtedly be disputed by some historians, rendered dubious by the absence of more precise documents, but so much evidence and proof must, in the end, be published in order to someone else to become interested and complete the puzzle.

NDLR : Gilles Perrault presented his expert report during a press conference on 27 October 2011 at the Maison des Arts et Metiers in Paris.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QcxFfnp5PL4

NOTES

[1] An alloy in tin or lead and antimony.

[2] Anne Rivière, co-author of a comprehensive catalogue of the works of Camille Claudel (among others), publisher Adam Biro.

[3] “in light of my investigations, I am now firmly convinced that, like you, this statuette could be a Rodin and that it dates from the time he worked with Camille Claudel. However, unfortunately, for the historian that I am, no document currently exists proving or disproving this hypothesis”.

[4] The G. H. case, Besançon CA judgment of 28 June 2001.

[5] The G. S. case, pending in the Paris Tribunal de Grande Instance [Regional Court].

[6] In twenty years, my various expert court reports have enabled me to examine 730 Rodin works and 56 Camille Claudel works.

[7] Rodin’s travel to Florence in 1874 then Rome in 1876

[8] “I have a small masterpiece that has for some time now perturbed what I customarily see, my mind and all of my experience. I owe it a profound debt of gratitude because it makes me think. This figure is from the same era as Venus de Milo. It provides me the same sensation as a powerful and full model, it has the same ease in the grandeur of its lines, which are, in fact, of reduced proportions. (…) the lovely shadows caress it (…) project the breasts, then fall asleep on the large stomach, boldly highlight the thighs. One of the arms, held to one side and behind, is overshadowed by a light tonal contrast. The movement of the other arm extends the cloth to the thighs, amassing an ardent shadow below the stomach.” Auguste Rodin in L’Art et les Artistes, no. 60, March 1910.

[9] Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, when interviewed by Gilles Perrault, found this inversed hand to be ugly and soft and not one produced by the master sculptor. Gilles Perrault noted that the softness seen resulted from a flattening of the thumb occurring after the work had been created. This pressure comes from molding or a hand on the original wax. Such accident was not repaired before casting, maybe with its creator’s knowledge.

[10] Modeling or sculpting tool used on stone to produce parallel grooves.

[11] Dominique Bona, Camille et Paul: La passion Claudel, ed. Grasset, Paris 2006

[12] ‘The contract’: letter of 12 October 1886 (Rodin Museum archives, Inv. L. 1452)

[13] Letter from Rodin to Camille (Rodin Museum archives, Inv. L. 1451)

[14] Comments passed on by one of his grand-children, interviewed by R. M. P. (D. Bona, Camille et Paul: La passion Claudel, ed. Grasset, Paris 2006, p. 187)

[15] Letter of December 1893 sent to Paul Claudel (French authors’ manuscripts association)

Photographic credits All photos : © G. Perrault

Except : © Musée Rodin

Photo 8 – Inv. D2016 Portrait of Séverine – Auguste Rodin – circa 1893 – Charcoal on cream paper 31,6 x 23,6 cm – Jean de Calan – Rodin Museum, Paris.

Photo 5 – Inv. D2156 Nude woman leaning left – Auguste Rodin – circa 1890 ? – Graphite pencil, quill and brown ink on watermarked, cream, paper – 20,2 x 12,7 cm – Rodin Museum/Adagp (1986), Paris.

Photo 7 – Inv. D 2857 Portrait de Séverine – Auguste Rodin – circa 1893 – Charcoal and grey wash on watermarked cream paper – 32 x 24,7 cm – Jean de Calan – Rodin Museum, Paris.

Photo 2 – Inv. D2916 Nude woman standing, frontal view, a cloth hiding her genitals – Auguste Rodin – Graphite pencil and rubdown on torn beige paper – 36 x 22,8 cm – Jean de Calan – Rodin Museum/Adagp (1986), Paris.

Photo 21 – Inv. D4102 Back view of nude woman, hands under her posterior – Auguste Rodin – circa 1906 et 1908 ? Crayon au graphite, estompe et aquarelle sur papier beige 32,4 x 25,2 cm – Jean de Calan – Rodin Museum/Adagp (1985), Paris.

Photo 4 – Inv. D4941 Standing nude woman – Auguste Rodin – Graphite pencil and water painting on cream paper – 40,5 x 28,8 cm – Jean de Calan – Rodin Museum, Paris.

Photo 3 – Inv. D5949 Standing nude woman, one hand on her stomach – Auguste Rodin – Graphite pencil on cream paper – 35,8 x 23 cm – Jean de Calan – Rodin Museum, Paris.

Photo 13 – Inv. D5996 Hand on genitals – Auguste Rodin – Graphite pencil, rubdown effect, on cream paper – 20 x 31 cm – Jean de Calan – Rodin Museum, Paris.

Photo 27 – Photo 936 Eustache de Saint Pierre – Victor Pannelier – circa 1886 – Albumen paper – 34,6 x 20 cm – Rodin Museum, Paris.

Rapport d’expertise